For many years I have been unconcerned about the Fed's conduct of monetary policy. To be fair, neither has the market (inflation expectations priced into Treasury notes have been subdued), and neither have legions of economists who have noted that the inflationary impetus of the Fed's expansive monetary policy has been kept in check by the decidedly and protracted sub-par rate of economic growth (~2% per year) over the past decade or so.

Nevertheless, my reasons for being unconcerned are distinctly different from the prevailing view. I think inflation has been held in check by the public's apparently voracious demand for money and money equivalents. The Fed has not so much flooded the market with liquidity as it has supplied money—sometimes reluctantly—in order to satisfy the public's desire for money. As Milton Friedman taught us, when the supply of money is matched by the demand for money, no inflation results.

In any event, the Fed has not "printed" money with abandon, since it has simply transmogrified notes and bonds into T-bill equivalents by buying them and paying for them with bank reserves, which are not money in the traditional sense, since they can only be held by banks. Banks have apparently been quite happy to hold on to the more than $3 trillion of bank reserves that the Fed has issued this past year, because those reserves are an attractive asset (default free) and they pay a floating rate of interest (the Fed funds rate). Simply put, the Fed has taken in notes and bonds (which are in abundant supply, thanks to trillion-dollar deficits) and exchanged them for T-bill equivalents, which have been in short supply. Nothing at all wrong with that.

Banks used their strong cash inflows during the onset of the Covid crisis—in the form of increased bank savings deposits and checking accounts—to purchase the notes and bonds which they then sold to the Fed.

More recently, I've become concerned that the return of confidence and a rebounding economy would result in a decline in the public's demand for all that money, and that the Fed would be slow to react with offsetting measures: a) higher short-term interest rates, which would work to boost the demand for money, and/or b) a reversal of its quantitative easing (which would withdraw unwanted bank reserves from the financial system). Per Friedman, that is the classic recipe for a rising price level (i.e., create a surplus of money relative to the demand for it). So far, the Fed seems determined to do just that—to ignore (and even welcome!) signs of declining money demand and rising inflation. Moreover, they fully intend to keep purchasing more notes and bonds in the months ahead. It's getting increasingly likely that the supply of bank reserves will exceed banks' desire to hold them as assets. Going forward, banks could well begin to expand their lending (abundant reserves make this possible), which is a sure-fire way to increase the amount of money in the economy. A future tsunami of money would almost certainly "float" higher prices for just about everything.

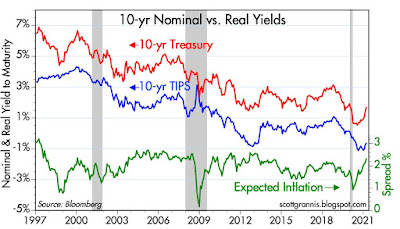

To once again be fair, the market is also beginning to get concerned about rising inflation: inflation expectations over the next 5 years have risen from 0.5% last summer to now over 2.5% per year (see Chart #1 below). What I'm saying is that there could be a lot more of this in the future.

Today Congress sent a $1.9 trillion spending bill to President Biden's desk, and he will almost certainly sign it in short order. In deja vu fashion, it passed very narrowly without a single Republican vote—just like Obamacare. In my view, it will do just about everything wrong. Far from "stimulating" the economy, it will instead greatly expand the welfare state and greatly increase the power of the federal government. Worse still, it will artificially inflate demand for just about everything but larger checking and savings deposits. Taking money from the economy (by selling notes and bonds) can't possibly stimulate the economy, just as taking a bucket of water from one end of a swimming pool and dumping it in the other end won't raise the water level. A lot of the money dished out by the bill is going to end up being used by people paying higher prices for all sorts of things. We see the beginnings of this already in, for example, the market for used cars (see Chart #4 below).

The economy doesn't need more demand, it needs more people working and more businesses reopening. Paying more to those who are still unemployed (plus exempting those higher unemployment benefits from taxation, as the bill does) won't encourage them to return to work. On the contrary, it will unnecessarily prolong the return to full employment. Many workers will surely discover that they can earn more (after-tax) than they could by going back to work. See my friend Steve Moore's

estimates of just how pernicious this could be. And do subscribe to his daily

newsletter, which has gobs of depressing facts and statistics.

The economy undoubtedly will get a boost in the months to come, but mainly because the Covid crisis is in rapid retreat. Daily new cases in the US are down almost 80% since the peak of mid-January. In California, they are down an astonishing 90% over the same period. We are rapidly approaching herd immunity, with estimates that upwards of 50-60% of the population has by now acquired immunity, either through infection, innate immunity (T-cells), or vaccination.

As is to be expected, by the time politicians rush in to supply aid to an ailing economy it is no longer needed. Moreover, it is counter-productive. Politicians almost always screw things up. That's why I'm a libertarian: we need less government, not more, to solve our problems.

Chart #1

Chart #1 shows the level of 5-yr nominal (red) and real (blue) Treasury yields, along with the difference between the two (green) which is what the bond market expects annual CPI inflation to average over the next 5 years. This latter has jumped from 0.5% last summer to now over 2.5%. Note that virtually all of the rise in inflation expectations is due to the rise in nominal yields. Real yields are very low, and they have barely budged; that's a sign that the rise in rates is not due to increased growth expectations—it's mostly due to increased inflation expectations.

Chart #2 shows how gasoline prices have surged in recent months. People are driving more, economic activity is on the rise, and oil prices have risen as demand challenges supply.

Chart #3

But as Chart #3 suggests, while higher oil and gasoline prices will certainly contribute to rising inflation, there are other, more powerful forces also at work. Rising inflation expectations far exceed the contribution to inflation resulting from higher oil prices.

As Chart #4 shows, used car prices have exploded since last summer. Extra cash seems to be burning holes in many consumers' pockets, and that could be fueling the rise in prices.

Chart #5 compares the yield on 10-yr Treasuries (red) with the ratio of copper to gold prices (blue). Both of these variables tend to rise and fall as economic growth prospects improve and deteriorate. This market-based indicator is telling us that there is a lot of construction activity (copper demand) going on around the world, and the bond market is sensing that the prospects for an increase in nominal activity have improved from last summer's abysmally low levels.

Chart #6 is a long-time favorite of mine, if only because it shows how tightly correlated the prices of these two assets (gold and TIPS) have been for the past 15 years. (I use the inverse of the real yield on TIPS as a proxy for their price.) It also suggests that gold prices tend to move in advance of TIPS prices. Right now that is telling us that TIPS prices are likely to decline (as real yields rise) in the future, but not by a whole lot. I would fully expect a big rise in real yields to happen at some point in the foreseeable future, either as a result of a stronger economy and/or a Fed tightening (which in turn would likely be a response to an unpleasant and/or unwanted increase in inflation). It's also interesting that gold prices have declined so much in the past year at the same time inflation expectations have risen. Gold is an imperfect inflation hedge, to say the least. Gold these days is likely being challenged by stronger growth expectations and the prospect of a tighter Fed in the future.

As I've said in earlier posts, although there is no shortage of reasons to be concerned about the future—number one being a significant rise in inflation followed by a Fed tightening response—I don't think things will collapse for at least the next 3-6 months. Indeed, there is every reason the economic landscape should brighten in the months ahead as the Covid crisis fades into history. It's unfortunate that the government seems hell-bent on doing the opposite of what is needed, but despite all the damage that may be done by the stimulus bill, a rebounding US and global economy—and higher prices—should provide significant support to the equity market.

And besides, what alternative is there, if cash yields zero? The expected return on cash is virtually guaranteed to be negative, as inflation rises and the purchasing power of cash declines. And don't forget that equities give you exposure to a rising price level, just as real estate does. As I've said repeatedly, what the Fed is telling you to do its "borrow and buy." The Fed wants you to shun cash, and the Fed almost always gets what it wants eventually.