All throughout 2017 the world worried that Trump and the Republicans were going to prove incompetent. Was Trump crazy? Could he actually govern? Could the Republicans abolish Obamacare as promised? Could they pass tax reform? Turns out they did a pretty good, if far from perfect, job. Obamacare is being dismantled, beginning with the elimination of the mandate. Tax reform could have been better, but it achieved its main objective: to stimulate investment. Meanwhile, hidden behind the distractions of tweet storms and faux pas, Trump has accomplished a major reduction in federal regulatory burdens. This can really make a difference over the long haul, and it may already be contributing to faster growth.

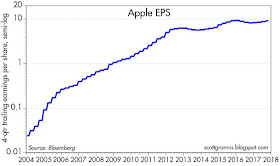

If 2017 was about just one thing, it was the ability of the Republicans to pass meaningful tax reform. The market spent most of the year handicapping the odds of tax reform, and it would appear that it is now mostly, if not fully, priced in. The tax reform package boils down to a one-time 20% boost to after-tax corporate profits (by cutting the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%), and that's pretty much what we have seen happen to equity prices this past year.

If 2018 is going to be about just one thing, it will be whether boosting the after-tax rewards to business investment results in a stronger economy. Beginning in 2009, Obama and the Democrats gambled that a massive redistribution of income would boost demand and thus boost the economy, but they lost. They ended up flushing $8 trillion down the Keynesian toilet. Trump and the Republicans are now gambling that a significant increase in the after-tax rewards to business investment will boost the economy. Only time will tell, but there are already hints of a stronger economy in the data: e.g., capex is up, industrial production is up, business confidence and the ISM indices are up, and industrial metals prices are up. It's likely that the current quarter could mark the first time we've enjoyed three consecutive quarters of 3% or more growth in over 12 years.

I think the meme for 2018 will be this: waiting for GDP. If the economy shows convincing and durable signs of stronger growth, more investment, more jobs, and rising productivity, then the Republicans' gamble will have paid off. If not, the Democrats will have carte blanche to take control of Congress and oust a sitting president.

From my supply-sider's perspective, we now have the essential ingredients for a stronger economy in place. Tax incentives are correctly aligned to encourage more business investment; regulatory burdens are being slashed, business confidence is high, and the Fed is not a threat for the foreseeable future. Swap and credit spreads are low, as is implied volatility, and that tells us that liquidity is plentiful and systemic risk is low. The fact that the rest of the world is also doing better as well is just icing on the cake.

But, argue the skeptics, won't businesses just use their extra profits to buy back shares and increase their dividends, making the wealthy even wealthier without creating any new jobs? This oft-repeated allegation is an empty argument, because it ignores one key thing: what do those who receive the money from buybacks and dividends do with it? John Cochrane explains it in this brief excerpt (do read the whole thing):

Suppose company 1 gets a tax cut, doesn't really know what to do with the money -- on top of all the extra cash the company may already have -- as it doesn't have very good investment projects. It sends the money to shareholders. Well, what do shareholders do with it? (Hint: track the money.) They most likely roll the money in to other investments. They find company 2 that does need the money for investment, and send it to that company. In the end, they only consume it if nobody has any good investment ideas.

The larger economic point: In the end, investment in the whole economy has nothing to do with the financial decisions of individual companies. Investment will increase if the marginal, after-tax, return to investment increases. Lowering the corporate tax rate operates on that marginal incentive to new investments. It does not operate by "giving companies cash" which they may use, individually, to buy new forklifts, or to send to investors. Thinking about the cash, and not the marginal incentive, is a central mistake.

In other words, what some companies do with their extra cash is immaterial. What matters is that tax reform has increased the marginal incentive to invest—for the entire economy—by reducing tax rates and by allowing the immediate expensing of capex. On the margin, investment now has become more attractive and more profitable in the US, and this will almost certainly result in more investment (some of which is likely to come from overseas firms deciding to relocate here), which in turn means more jobs, more productivity, and higher real incomes. As I explained a few years ago, productivity has been the missing ingredient in the current lackluster recovery, and very weak business investment is one reason that productivity has gone missing. A pickup in investment is bound to raise productivity, which is the ultimate driver of growth and prosperity.

So it's clear to me that tax reform is a big deal, because it's very likely to boost the long-term growth trajectory of the US economy by a meaningful amount. Surprisingly, however, the market does not appear to share that view. Why else would real yields still be miserably low (e.g., 0.3% for 5-yr TIPS)? Why else would the market expect only a modest increase (0.75% or so) in the Fed's target funds rate for the foreseeable future? The current Fed target is 1.5%, while 2-yr Treasury yields, which are the market's expectation for what that rate will average over the next two years, are only 1.9%. As for real yields, the current Fed target translates into a real yield—using the PCE Core deflator—of roughly zero, while the yield on 5-yr TIPS says the market expects that rate to average only 0.3% over the next 5 years. If the economy really gets up a head of steam (e.g., real growth of 3% or more per year), I can't imagine the Fed wouldn't raise rates by more than the market currently expects, and I can't imagine nominal and real yields in general won't be significantly higher than they are today. The last time the economy was growing at 4% a year (early 2000s), 5-yr TIPS real yields were 3-4%.

Yet the Fed is the one thing I worry about, which is nothing new. The Fed has been responsible for every recession in recent memory, because each time they have tightened monetary policy in order to reduce inflation or to ward off an expected increase in inflation, they have ended up choking off growth. They are well aware of this, however, so they are going to be very careful about raising rates as the economy picks up steam. But as I've explained many times before, the Fed's worst nightmare is a return of confidence. More confidence in a time of surprisingly strong growth would almost certainly reduce the demand for money; if the Fed doesn't take offsetting moves to increase the demand for all those excess reserves in the banking system (e.g., by raising the funds rate target and draining bank reserves) the result would be an unwelcome rise in inflation. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon: when the supply of money exceeds the demand for it, inflation is the inevitable result. And higher inflation would set us up for the next recession.

On balance, I think it's quite likely the economy is going to improve, and surprisingly so. Ordinarily that would be great news for the equity market, since a stronger than expected economy should result in stronger than expected profits. But the market is still cautious, so good news is going to be met with increased skepticism: if the Fed raises rates as the economy improves, the market will worry that higher rates will increase the risk of recession. And even if the Fed is slow to raise rates, the market will see that as a sign that inflation is likely to move higher, and that would in turn increase the odds of more aggressive Fed tightening and eventually another recession. In short, we're probably going to see the market climb periodic walls of worry, just as it has for the past several years.

Risk assets should do well in this environment, given time, but there will be headwinds. Rising Treasury yields will act to keep PE ratios from rising further, so equity market gains are likely to be driven mainly by stronger-than-expected earnings. At the same time, higher bond yields will make it easier to people to exit stocks (very low yields today make being short stocks very painful).

Emerging market economies are so far behind their developed counterparts that they have tremendous upside potential in a world that is increasingly prosperous, but a stronger than expected US economy is likely to boost the dollar, which in turn would put pressure on commodity markets and the emerging economies that depend on them.

I continue to believe that gold is trading at a significant premium to its long-term, inflation-adjusted price (which I estimate to be around $600/oz.) because the world is still risk-averse. So a stronger US economy and a stronger dollar would spell bad news for gold. Who needs gold if real yields and real growth are rising?

In order to judge whether things are playing out in a healthy fashion, it will be critical to periodically assess the status of the world's demand for money—particularly bank reserves, of which there are over $2 trillion in excess of what is needed for banks to collateralize their deposits. If banks' demand to hold excess reserves declines faster than the Fed's willingness to drain reserves and/or raise the interest rate it pays on reserves, then higher inflation is almost sure to rear its ugly head. Signs of that happening would likely be seen in rising inflation expectations, a falling dollar, a steeper yield curve, and/or rising gold and commodity prices.

The world is on the cusp of a new chapter of stronger growth, led by US tax reform. The US economy has plenty of upside potential, given the past 8 years of sub-par growth and a significant decline in the labor force participation rate and lingering risk aversion. Tax reform can and should unleash that underutilized potential and boost confidence. The future looks bright, but there are, of course, lots of things that could go wrong (e.g., North Korea, the Middle East, Trump's ego, the Fed) so if and as the world becomes less risk averse, an investor would be wise to remain cautious, since very few things these days are obviously cheap. On the other hand, Treasuries, and bond yields in general, look very low and should thus be approached with great caution.