The force that moves markets is the unexpected. The economy has performed much better than expected, and that's why the stock market returned over 32.4% last year and 10-year Treasury yields rose 100 bps.

Although it's unlikely that things will improve so dramatically in the coming year, I remain optimistic. Despite the headwinds, there are some impressive positive forces at work: the inherent dynamism of the U.S. economy, the reduction in the size of government, the decline of risk aversion, and the significant increase in U.S. petroleum production. Many will likely disagree with me, but I see the ongoing failure of Obamacare as a big positive, since I think it ushers in a new era of thinking in which we become skeptical of attempts by the government to manage more of the economy, and more open to allowing free market forces to resolve problems.

Here are some charts which make interesting points that you might not see elsewhere:

This continues to be the weakest recovery ever. The "gap" between where the economy is today and where it could be if it had returned to its long-term growth trend (which is roughly 3% per year) is about 10% (see chart above). If this had been a typical recovery, national income would have been about $1.6 trillion higher than it is today. That's a lot of money—about $11,700 per working person—that's been left on the table, and that goes a long way to explaining why there is still a dearth of confidence and optimism.

As the first of the above two charts shows, quarterly growth rates in real and nominal GDP have been rather erratic in recent years, but there is a strengthening trend that is evident over the course of the past year. The second chart smooths things out by showing the 2-year annualized growth of real GDP. The economy has been growing at about a 2.5% annualized pace, on average, for the past four and a half years. Not very impressive, but somewhat better than the "new normal" economy which many expected to be 2% annual growth for as far as the eye could see.

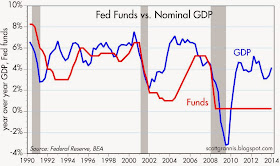

As the above chart shows, nominal GDP has been growing at about a 4% annualized pace since mid-2009. Ordinarily, the Fed would have kept short-term interest rates in a 2-3% range given this pace of growth. Instead, they have kept short-term rates near zero for over five years. That translates into an unprecedented degree of monetary policy accommodation. But as I've argued before, the Fed hasn't been "stimulative." It's more appropriate to view the Fed's policy actions as "accommodative." By buying trillions of notes and bonds and paying for them with bank reserves, the Fed has been accommodating the world's seemingly insatiable demand for "safe" assets. This is unlikely to continue much longer, because risk aversion is declining and the demand for money is no longer surging. Interest rates will move higher in coming years, and it's only a question of when and how fast.

The chart above shows one measure of money demand: the ratio of M2 to nominal GDP. Think of that as the portion of the average person's annual income that he or she wishes to hold in the form of readily spendable cash. The ratio (the demand for money) increased rapidly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, as almost everyone struggled to deleverage and/or boost savings. Over the past year, however, money demand by this measure has only increased by 1% or so. Most of the increase in M2 relative to nominal GDP since 2008 can be accounted for by a $3 trillion increase in bank savings deposits, and most of those savings deposits are now backed up by bank reserves. Banks effectively took in $3 trillion of new deposits and handed the money over to the Fed in exchange for bank reserves. People were willing to accept almost nothing in the way of interest on their deposits, and banks were unwilling to lend to anyone but the U.S. government, even though it left them with a negligible spread.

One of the most extraordinary developments in the current recovery has been the dramatic closing of the fiscal gap. Government spending relative to GDP has collapsed, mainly because nominal spending has not increased at all since mid-2009. Meanwhile, revenues have increased at a faster rate than nominal GDP, thanks mainly to an expanding tax base (i.e., more people working, rising incomes, more corporate profits, more capital gains realizations).

As a result, in the space of just four and a half years, the federal deficit has fallen by almost two-thirds in dollar terms. Not one single person in the world thought that anything like this would or could happen. Four years ago the federal deficit was projected to be measured in trillions of dollars per year for as far as the eye could see. Now it's back down to levels that are easily manageable. There remains the concern, of course, that entitlement spending is likely to soar in coming years, so we are not out of the woods yet. But this is still incredibly welcome news.

What we have learned over the past 4-5 years is very important. Government "stimulus" spending doesn't work. Transfer payments don't boost economic growth. The government spending multiplier is almost certainly less than one (i.e., one extra dollar of government spending is likely to add less than one dollar to GDP, and in all likelihood, could actually subtract from GDP). Fiscal "contraction" (i.e., a decline in government spending) doesn't necessarily hurt the economy and can even help, by giving the private sector more breathing room. And most importantly, government cannot possibly manage entire industries (e.g., healthcare) better than the private sector can. All of this knowledge and evidence will add up in coming years to a positive end: less government interference in the economy. And that, in turn, will be the best kind of stimulus for the economy.

The present is still disappointing, but the future is looking much brighter.