Friday, April 29, 2011

Inflation update

On a year-over-year basis, inflation according to the Personal Consumption Deflator remains within the Fed's target range.

On a shorter time frame, however, the pace of inflation is picking up. Over the past six months, the headline PCE deflator is up at a 3.4% annualized rate, and the Core PCE deflator over the past three months is up at a 1.9% annualized rate. The fact that both headline (total) and core inflation (ex-food and energy) are rising at a faster rate at the same time is consistent with the fact that the Fed is indeed in an accommodative mode, and willing (and wanting) to let all prices rise. They are getting their wish, which is not surprising. The rise in measured inflation is still relatively tame, however, but it will be very important to see how this unfolds in coming months.

This last chart shows the major sub-components of the PCE Deflator (services, durables, and non-durables). Since 1995, headline inflation has been subdued by a previously-unprecedented decline in durable goods prices (i.e., this is the first time in the history of this series that the blue line has declined on a sustained basis). It is probably not a coincidence that 1995 marked the first year in which China pegged its currency to the dollar (thus stabilizing and eventually strengthening it), which in turn set the foundation for strong export-led growth. This chart also helps explain why there is so much confusion over whether we should worry about inflation or deflation, since there is evidence of both.

The chart also tells a very interesting story. Since 1995, service sector prices have risen by 55%, while durable goods prices have fallen by 26%, for a 110% relative price change (this is roughly equivalent to saying that one hour's worth of work in the service sector today buys twice as much in the way of durable goods as it did in 1995). To the degree that China's exports of durable goods have contributed to this relative price shift, it is a testament to how the increased productivity of the Chinese workforce has resulted in a significant rise in living standards for workers in the industrialized world. Contrary to what uninformed critics say, global trade is a win-win situation for all concerned.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Putting the claims number in perspective

I wasn't going to post on this subject today, but then I saw comments to the effect that today's jobless claims numbers were "ugly." I think it's hard to look at this chart and find anything ugly about it. To be sure, claims have ticked up in recent weeks, but that sort of volatility comes with the territory. Plus, nonseasonally claims (actual claims) have been flat for the past two months; the seasonally adjusted number has risen because actual claims haven't fallen as they typically do at this time of the year. The "ugliness" of the jobs numbers could be simply a seasonal adjustment artifact.

And consider this chart: the number of people receiving unemployment insurance has been steadily decreasing all year. Continuing claims for unemployment have in fact declined by slightly more than 1 million year to date. Undoubtedly, some of those people are now without jobs and without insurance, but it's equally true that even more are now likely working. After all, payrolls have been increasing for over a year.

The jobs market is slowly improving; while it may be disappointingly slow progress, it is far from ugly.

Deflation is dead

With today's release of first-quarter GDP, we see that the GDP deflator, the broadest measure of inflation available, has clearly turned up. Deflation risk was palpable in 2009, as the deflator neared zero, but it's now history. Deflation is dead, and the only uncertainty about the outlook for inflation is how high it will be in coming years.

With the death of deflation risk, the outlook for equities and corporate bonds has brightened. Deflation means shrinking cash flows and shortages of money, and both of those are bad for equity and corporate bond holders. Eliminating that risk increases the expected returns from future cash flows, even if the growth of those future cash flows might seem otherwise unimpressive.

What this recovery has taught us

This chart compares the long-term trend growth of real GDP to actual GDP, with today's Q1/11 GDP release included. What jumps out from the chart is the fact that the economy's level of output has been about 10% below its long-term "potential" output for more than two years. This is the biggest growth shortfall since the Depression, and it has persisted for more than two years despite unprecedented levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus.

Die-hard Keynesians are still unwilling to accept that stimulus has failed, and some, like Paul Krugman, still argue that the problem was that the stimulus wasn't big enough. But as I predicted in a post in January 2009, the fiscal stimulus package championed by Obama and the Democrats would prove to be a significant drag on growth, and I think the evidence now supports my prediction. You can't create growth out of thin air, or by transferring money from one person to another by government fiat. When government commandeers a big chunk of the economy's resources, as it did beginning two years ago, those resources end up being spent in a much less efficient fashion than if they had been left in the private sector. The result is slower growth. We're in a recovery, but it's a very slow recovery because government is smothering the economy.

Morever, with trillion-dollar deficits staring us in the face for as far as the eye can see, market participants, workers, and business owners can't help but fear an eventual and substantial rise in future tax burdens. Just the possibility that future tax burdens could rise meaningfully is enough to reduce the discounted, after-tax, present value of future cash flows, and to discourage, on the margin, new investments.

Monetary policy is also culpable. By adopting an unprecedented quantitative easing program, and promising repeatedly to keep short-term rates very low for an extended period, the Fed has introduced a significant amount of monetary uncertainty into the financial markets and the economy. Inflation expectations are rising, and the dollar has fallen to all-time lows, as capital decides that the U.S. economy is not a very attractive place to be. Treasury yields are still very low, despite our massive budget deficit, because an excess of spending is depressing the economy and depressing the expected returns on alternative investments.

So the lesson from this tepid recovery is that the more government tries to "stimulate" the economy, the worse things will be. If Washington and the American people can take this lesson to heart, then the pain and suffering of this slow-growth recovery will not have been in vain. This could end up being the best thing to have happened for the economic outlook since the early 1980s.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Bernanke and the dollar

In his first-ever press conference today following the FOMC meeting, Fed Chairman Bernanke mentioned the dollar quite a few times. You might think that would be a natural, coming from the head of the institution that has direct control over the supply of dollars to the world, and by extension the dollar's value. But in fact, the Fed rarely addresses the issue of the dollar's value in the context of the things it watches or tries to target.

So it was somewhat refreshing that today Bernanke joined with Geithner and Treasury Secretaries of the past in saying that a strong and stable dollar was in the interests of both the U.S. and the global economy. Unfortunately, he qualified that by adding that he thought the dollar's recent weakness was another one of those transitory things (like rising headline inflation and weak first quarter growth) that should reverse in the medium term. He's not targeting the dollar directly, in other words, believing instead that the dollar will find support and prove strong and stable over the long run if the Fed is successful at containing inflation and boosting the economy.

It's all too tautological for me, and for the markets, I suspect. Yes, if the Fed is successful in defending the dollar's purchasing power over time, then the dollar should find market support and its value should be relatively strong and stable. But just how are we going to get a stronger dollar tomorrow by weakening the dollar today?

As I've pointed out, the Fed has yet to commit any gross monetary error, since there is no sign of any unusual growth in the M2 money supply. But even though M2 is only growing at a a 6% rate, the decline in the dollar's value against other currencies and gold is prima facie evidence that the Fed is supplying more dollars to the world than the world is demanding. It's clear that monetary policy is accommodative, and that means the Fed is setting interest rates artificially low in order to create an over-supply of dollars, and an over-supply of dollars means the dollar's value has to decline.

This is what is troubling the world. How can we be sure that the Fed will be able to pull off the trick of weakening the dollar today in order to strengthen it tomorrow? A weaker dollar risks letting the inflation genie out of the bottle, and we know it's very hard to put back in once that happens. There is little or no theoretical or logical support for the idea that a weaker currency creates a stronger economy. Bernanke is saying the right things, but he is also asking us to trust him an awful lot. The world would feel much better if he were more specific. Holding press conferences is a good way to make the Fed more transparent, but unless there is substance (i.e., rules and/or objective measures that guide policy) behind the words, then fear, uncertainty and doubt will erode confidence in the dollar and that will exacerbate inflationary pressures. Less demand for dollars contributes to an over-supply of dollars the same way an increased supply does. In the end it's a negative feedback loop that threatens us all.

So it was not surprising to see the dollar decline in the wake of today's FOMC meeting (9:30 am Pacific Time on the chart above) and throughout Bernanke's testimony, and it was not surprising to see gold prices rise (see below). In nominal and real terms against a broad basket of currencies, the dollar is now at a new all-time low. In nominal terms gold is at a new all-time high, but in real terms it is still about one-third below the highs it (very) briefly reached in early 1980.

Ben "Trust Me" Bernanke may well pull off the greatest balancing act in history when all is said and done, but I have to believe there is an easier and more direct way to achieve a strong and stable dollar, which is ultimately the only way to enjoy low and stable inflation and a strong economy.

So it was somewhat refreshing that today Bernanke joined with Geithner and Treasury Secretaries of the past in saying that a strong and stable dollar was in the interests of both the U.S. and the global economy. Unfortunately, he qualified that by adding that he thought the dollar's recent weakness was another one of those transitory things (like rising headline inflation and weak first quarter growth) that should reverse in the medium term. He's not targeting the dollar directly, in other words, believing instead that the dollar will find support and prove strong and stable over the long run if the Fed is successful at containing inflation and boosting the economy.

It's all too tautological for me, and for the markets, I suspect. Yes, if the Fed is successful in defending the dollar's purchasing power over time, then the dollar should find market support and its value should be relatively strong and stable. But just how are we going to get a stronger dollar tomorrow by weakening the dollar today?

As I've pointed out, the Fed has yet to commit any gross monetary error, since there is no sign of any unusual growth in the M2 money supply. But even though M2 is only growing at a a 6% rate, the decline in the dollar's value against other currencies and gold is prima facie evidence that the Fed is supplying more dollars to the world than the world is demanding. It's clear that monetary policy is accommodative, and that means the Fed is setting interest rates artificially low in order to create an over-supply of dollars, and an over-supply of dollars means the dollar's value has to decline.

This is what is troubling the world. How can we be sure that the Fed will be able to pull off the trick of weakening the dollar today in order to strengthen it tomorrow? A weaker dollar risks letting the inflation genie out of the bottle, and we know it's very hard to put back in once that happens. There is little or no theoretical or logical support for the idea that a weaker currency creates a stronger economy. Bernanke is saying the right things, but he is also asking us to trust him an awful lot. The world would feel much better if he were more specific. Holding press conferences is a good way to make the Fed more transparent, but unless there is substance (i.e., rules and/or objective measures that guide policy) behind the words, then fear, uncertainty and doubt will erode confidence in the dollar and that will exacerbate inflationary pressures. Less demand for dollars contributes to an over-supply of dollars the same way an increased supply does. In the end it's a negative feedback loop that threatens us all.

So it was not surprising to see the dollar decline in the wake of today's FOMC meeting (9:30 am Pacific Time on the chart above) and throughout Bernanke's testimony, and it was not surprising to see gold prices rise (see below). In nominal and real terms against a broad basket of currencies, the dollar is now at a new all-time low. In nominal terms gold is at a new all-time high, but in real terms it is still about one-third below the highs it (very) briefly reached in early 1980.

Ben "Trust Me" Bernanke may well pull off the greatest balancing act in history when all is said and done, but I have to believe there is an easier and more direct way to achieve a strong and stable dollar, which is ultimately the only way to enjoy low and stable inflation and a strong economy.

Capital goods orders take a breather

New orders for capital goods rose by a strong 3.7% in March, and February orders were revised upwards by 2% (upward revisions of past data have become quite common in this series over the past year), but that wasn't enough to offset the big decline in January orders. Thus the annualized growth rate of this series over the past 6 months has slipped to 4.8%, down from the heady 20+% pace of last year's third quarter. The 3-mo. moving average (shown here) also reflects this slowdown. Still, capex orders have surged 25% in the past two years, and that is pretty impressive by any standard. Whether the recent slowdown/slump is anything more than payback for the unprecedented growth spurt of last year remains to be seen, but that would be my guess at this point.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Geithner's cognitive dissonance

Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner today said that "a strong dollar is in our interest as a country," even as the dollar plumbed new, all-time, nominal and real lows against a large basket of other currencies.

We can only hope that this week's FOMC meeting will find our Fed governors less clueless about the reality of what is happening to the dollar. The dollar has never, ever, been so weak, and it's no coincidence that U.S. monetary policy has never been so expansive and so fraught with uncertainty.

The seventh fatal flaw of ObamaCare

This post from last November summarizes six fatal flaws of ObamaCare, and I have related comments here. Yesterday the WSJ ran an article by Daniel Kessler, "How Health Reform Punishes Work," which exposes a fatal flaw that I had not fully appreciated before: the devastating impact of government healthcare subsidies on effective marginal tax rates for the middle class. Some excerpts:

In other words, the existence of sizable subsidies would create extremely high marginal tax rates for a large number of people. Many families could find themselves in a situation where working more or getting a pay raise would actually (and significantly) reduce their take-home pay. This would be not only damaging to the economy and our living standards, but unacceptable from the point of view of simple logic and basic notions of fairness. It's a trap, not a subsidy. Memo to starry-eyed liberals: subsidies may sound like a great way to redistribute income, but they bring with them a host of unintended, perverse, and outrageous consequences.

The health law establishes insurance exchanges—regulated marketplaces in which individuals and small businesses can shop for coverage—and minimum standards for the insurance policies that can be offered. Because the policies will be so costly, there's a subsidy for buyers that phases out as family income rises. This sounds reasonable—but the subsidies required to make a "qualifying" insurance policy affordable are so large that their phaseout creates chaos.

Starting in 2014, subsidies will be available to families with incomes between 134% and 400% of the federal poverty line. For example, a family of four headed by a 55-year-old earning $31,389 in 2014 dollars (134% of the federal poverty line) in a high-cost area will get a subsidy of $22,740. A similar family earning $93,699 (400% of poverty) gets a subsidy of $14,799. But a family earning $1 more—$93,700—gets no subsidy.

Consider a wife in a family with $90,000 in income. If she were to earn an additional $3,700, her family would lose the insurance subsidy and be more than $10,000 poorer.

To phase out the subsidy smoothly for families with incomes of 134% to 400% of poverty, the law would have to take away $22,700 in subsidies as a family's income rose to $93,700 from $31,389. In other words, for every dollar earned in this income range, a family's subsidy would have to decline by 36 cents. On top of 25% federal income taxes, 5% state income taxes, and 15% Social Security taxes, this implies a reward to work of less than 20 cents on the dollar—in economists' language, an implicit marginal tax rate of over 80%.

In other words, the existence of sizable subsidies would create extremely high marginal tax rates for a large number of people. Many families could find themselves in a situation where working more or getting a pay raise would actually (and significantly) reduce their take-home pay. This would be not only damaging to the economy and our living standards, but unacceptable from the point of view of simple logic and basic notions of fairness. It's a trap, not a subsidy. Memo to starry-eyed liberals: subsidies may sound like a great way to redistribute income, but they bring with them a host of unintended, perverse, and outrageous consequences.

Real estate update -- more and more attractive

This chart shows two different measures of housing prices, as calculated by the folks at Case Shiller and Radar Logic. Both are showing some softness in pricing in recent months (but they both report prices 2-3 months after the fact), and this appears to be raising concerns in the market about whether housing is entering a new downturn. I'm not as worried about that as I am impressed by how similar the two indices are, by how relatively stable they have been for the past two years, and by the fact that both show the housing price bust to have been of roughly the same magnitude (Case Shiller -31%, Radar Logic -36%).

Let's stipulate, based on this information, that housing prices in major markets across the U.S. have fallen by one-third from the high they reached in 2006. In real terms, that works out to approximately a 40% decline, as shown in the next chart. Over the same period, disposable personal income has risen by about 15%, and 30-yr fixed mortgage rates have fallen from 6.5% to 4.8%. Do the math however you want, that adds up to a gigantic decline in the cost for the average family of buying a home (available measures of housing affordability show that homes have never been so cheap). Maybe housing prices are going to fall another 10%, who knows? But prices have already fallen by several orders of magnitude, and another 10% is not going to make much of a difference in the long run, especially if the Fed succeeds in reflating the economy. A sustained rise in inflation, coupled with what could easily be a housing shortage (given the extremely low level of new home construction relative to new housing formations) could translate into hefty gains for housing prices over the next 5-10 years.

This last chart compares the Case Shiller measure of home prices to Moody's Commercial Property Index. According to this latter measure, commercial real estate has suffered an even greater decline (-45%) than housing prices, with commercial property values having erased all the gains of the past decade. Maybe prices will slip a bit further before this is all over, but there's no denying that there has been a humongous price adjustment. Surely the lion's share of the downward price action is now water under the bridge.

What strikes me most about the action in the real estate market is that it is the opposite of the action in the gold and commodities market, yet real estate, gold, and commodities are all classic inflation hedges. If inflation is heating up and the Fed has trouble reining it in, I have to believe that a rising inflation tide would provide strong support for all tangible asset prices, especially real estate. Of all the things available to an investor who is worried about inflation, commercial real estate looks like the cheapest inflation hedge out there.

Full disclosure: I am long VNQ and a few miscellaneous REITs at the time of this writing.

Confidence improves, but still very low

Consumer confidence picked up a bit in April, according to the Conference Board's survey, but as this chart reminds us, confidence is still quite low from an historical perspective. Consumer confidence is not a leading, but rather a lagging indicator, so the value of this information is rather limited. But it does underscore the points I've been making for a long time, namely that there is no shortage of pessimism out there, no shortage of things to worry about, and it's difficult to find any signs of "irrational exuberance" in market pricing. The market, like the public in general, is still climbing walls of worry. This gives the edge to bulls, as long as the economy avoids significant deterioration.

Monday, April 25, 2011

Gold and commodities update

As this chart shows, gold has a tendency to lead the price action in commodities. This in turn suggests that there is a monetary common denominator that is at work behind the scenes. Many—including the Fed—argue that commodity prices are rising solely because of strong demand in emerging market economies that has outstripped supply, but that doesn't explain why demand for gold should have arisen first, and so strongly. Nor does it explain why the prices of hundreds of commodities should be moving together, nor why thousands of commodity producers should have been outfoxed by demand all at the same time. Then there is the coincidence that gold and commodities started to rally in 2001, which just happened to be when the Fed started easing in earnest, after having pursued a very tight policy for the previous 5-6 years. And let's not forget that the dollar peaked in early 2002, and has been trending down ever since.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

Bank reserves update

Just a quick post to once again revisit the issue of whether or not the Fed is "printing" massive amounts of money and thus threatening the world with some sort of financial Armageddon. This chart compares total bank reserves with excess reserves. The two series move in lockstep. Reserves have increased by about $1.45 trillion since Sep. '08, and Excess Reserves have increased by about $1.43 trillion. In other words, banks have effectively decided to hold on to virtually all of the increased reserves that have flooded the system. One big reason they are doing this is that reserves now pay interest, whereas before they didn't. That makes reserves a close substitute for T-bills. The Fed has essentially accommodated banks' desire to reduce the risk inherent in their balance sheets. As long as banks continue to hold their reserves and not use them to greatly expand the money supply, the Fed is not "guilty" of printing money. In order to tighten monetary conditions, the Fed can either withdraw those reserves by selling its massive holdings of Treasuries and MBS, or it can simply raise the interest rate it pays on reserves. Mark Perry has a similar post which adds to the discussion.

Greece will default, the only question is by how much

With Greek 2-yr debt trading at a yield of 22%, and spreads to Germany at record highs, the question the market is grappling with is not whether Greece will default, but by how much. As the chart below shows (HT: Zero Hedge), long-dated Greek bonds are now selling for 50-60 cents on the dollar, suggesting the market is expecting a default/restructuring that effectively reduces the amount Greece owes by almost half. We've seen massive restructurings like this before (Argentina comes to mind) but despite the magnitudes involved, life goes on. When debt is wiped out or cut in half, lenders lose but borrowers gain, in a sense. It's a wealth transfer, but it doesn't necessarily reduce the world's output, which is what provides the foundation for all wealth and all cash flows. And not surprisingly, therefore, despite the near-certainty of a massive Greek restructuring, global stock markets remain very close to their recent highs, and swap spreads in the U.S. and Eurozone remain relatively low.

Continued marginal improvement in the labor market

Although weekly claims (chart below) recently have ticked up a bit, perhaps the more important news is that, as the chart above shows, the number of people receiving unemployment insurance has hit a new post-recession low. Progress is slow, but it's still progress.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Stocks struggle against gold

The top chart shows over 80 years of the monthly stock/gold ratio, while the bottom chart shows daily values over the past three years. Over long periods, stock prices have edged out gold prices, but the ratio can be extraordinarily volatile at times. If stock prices are a proxy for productive assets, and gold prices a proxy for physical (hard) assets, then its reassuring to see that productive activities are more profitable over time than speculative activities. But it's a very rocky road.

Stocks need sound and stable monetary policy to flourish, as they did from the 1950s through the mid-1960s (when inflation was very low and stable), and from the early 1980s through the late 1990s (when inflation fell from double digits to a relatively stable 2%). The problem with stocks today is rooted not only in the potentially inflationary consequences of Bernanke's easy money, but also in the potentially crushing burden of excessive government spending.

Silver goes hyperbolic

For bubble enthusiasts, I offer this chart of silver in today's dollars. Chartists would note that silver is going hyperbolic, and that's quite something since the y-axis is also logarithmic. Caveat emptor big-time. As with gold, speculators may make a quick 70% or so as prices soar to prior highs in real terms (bear in mind however that those previous highs for silver were quite artificial, since the Hunt brothers had managed to briefly corner the market), but the reversal that could follow in its wake promises to be breath-taking. This is heady stuff and only for the most steeled of professionals.

Mortgage applications on the rise

The top chart shows an index of mortgage applications (all types), and the bottom chart shows the history of 30-yr fixed mortgage rates. Late last summer I noted what looked to be a new buying uptrend underway, and now it looks like the real thing. There has been a 29% increase in new applications for mortgages since last July, even though 30-yr fixed mortgage rates have been higher than they were last summer for the past 5 months. (Actually that's the wrong way to characterize what has happened: demand for mortgages is not up despite the rise in mortgage rates—mortgage rates are up because of the rise in the demand for mortgages, and the strengthening of the economy in general.) All in all, a healthy sign of improving housing fundamentals.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Bank lending update

With the inflationary potential of the Fed's $1.5 trillion injection of reserves into the banking system apparently held in check by 1) banks' reluctance to lend and desire to strengthen their balance sheet with excess reserves, and 2) the world's apparent reluctance to borrow, it's vitally important to keep track of new bank lending. The easy way to do that is to watch the growth of M2, since that should reflect the net impact of any monetary expansion driven by new bank lending. But as my previous post detailed, M2 doesn't reflect any unusual expansion in the money supply to date.

The chart above, which focuses on bank lending to small and medium-sized businesses, is a more narrowly-focused look at bank lending, and it shows a clear and continuing uptrend in lending activity. It's still rather tepid, since this measure has only grown at a 7% annualized pace since December, but it marks an important inflection point and the start of a new lending cycle. Most importantly, it also reflects increased confidence on the part of banks and businesses, and that is a key ingredient for future growth in the economy.

Show me the money

I keep coming back to the issue of money, QE2, and inflation because it is so important.

Here's a summary/clarification of my most recent post on the subject, as well as other related comments I've made along the way:

There are still some important questions to be answered, however. How can there not have been any new money printed, if the Fed has purchased almost $1.5 trillion of Treasuries and MBS since late 2008? What happened to the $1.5 trillion that the sellers of those securities received? Can the quantitative easing process continue indefinitely without inflationary consequences? What will happen if/when quantitative easing stops?

The short answer to the first question (why no new money?) is that at the end of the day, two things happened: 1) banks were willing to hold on to the new reserves, and not use them to increase their lending, and 2) the world in aggregate did not want to increase its dollar borrowings. Another way to put this is that the extra reserves satisfied the world's demand for additional safe and liquid assets. At the same time, the Fed effectively swapped reserves (a kind of T-bill equivalent) for T-Notes and MBS, thus shortening the maturity of federal debt and reducing the private sector's exposure to rising interest rates.

Can this continue indefinitely without inflationary consequences? I doubt it. But there is a certain vicious-cycle aspect to all this that is troubling. The more the government borrows (with the federal deficit on track to hit 10% of GDP, a very large number by any standard), the more the government spends; the more the government spends, the less efficient the economy becomes; the less efficient the economy, the slower it grows; the slower the economy, the fewer attractive investment opportunities there are, and thus the more attractive Treasury debt becomes, even if interest rates are very low relative to inflation. This same dynamic may help explain why Japan has had deficits of more than 10% of GDP for many years, yet the yields on government bonds remain extraordinarily low and economic growth has been disappointingly slow.

Is the end of quantitative easing going to be painful? Not necessarily. The end of QE2 means only that the Fed will stop swapping reserves for longer-maturity securities. There will still be a mountain of excess reserves in the system. Even if the Fed were to start "tightening" immediately after the end of QE2, that "tightening" would hardly be considered problematic, since it could take years to reverse all the injections of reserves. And in lieu of actually reverse its reserve injections, the Fed could simply decide to pay a higher rate of interest on existing reserves. This would have the effect of raising short-term interest rates without reducing the supply of reserves. The steepness of the yield curve is proof that the market is already braced for short-term interest rates to rise by hundreds of basis points. The issue is not whether the Fed will tightening or by how much they will tighten; the issue is when and how fast they will start raising rates.

It is entirely conceivable that a rise in interest rates that results from a Fed tightening will have the effect of increasing the world's demand for longer-maturity securities, thus obviating the need for the Fed to continue swapping reserves for longer-maturity securities.

I hope it's clear that I'm trying to take an objective and dispassionate view of things. There is reason to be concerned, but not yet any reason to panic.

UPDATE: I want to clarify my views on inflation, since on the one hand I argue that the Fed hasn't committed an obvious monetary policy error (because M2 growth is still normal), but on the other hand I note the symptoms of rising inflation (weak dollar, rising gold and commodity prices) and worry that it will continue to rise. Contrary to what some conclude, I am not saying we don't have an inflation problem. I think that 6% M2 growth, if it persists, will be a strong force limiting the rise in reported inflation to 10% at the most, but even 5-6% inflation is enough to qualify as a problem in my book. With 6% M2 growth, inflation could exceed 10% only if we see a meaningful decline in money demand (M2/GDP) and a pickup in M2 velocity (GDP/M2). That is not impossible at all, but it has yet to occur.

Here's a summary/clarification of my most recent post on the subject, as well as other related comments I've made along the way:

The Fed has expanded bank reserves and the monetary base massively, creating the potential for hyperinflation. (In our fractional reserve banking system, each new dollar of reserves potentially can support about $10 new dollars of bank deposits.) But so far, none of this "money printing" has shown up in traditional measures of the money supply (e.g., currency, M1, and M2), which display no unusual level of growth in recent years. (In fact, they are growing at a much slower rate today than they did in the inflationary 1970s.) Indeed, virtually all of the reserves created by the Fed to pay for its security purchases are sitting idle, in the form of excess reserves, at the Fed.

Without a huge increase in the actual amount of money in the economy, we are unlikely to see a huge increase in inflation. Alternatively, a significant decline in the demand for money could support a rise in the price level, but there is no evidence to date that this is occurring (except for the fact that the dollar is trading at record lows).

Meanwhile, market-based and leading indicators of inflation strongly suggest that the Fed has supplied more money to the world than the world wants (e.g., the extreme weakness of the dollar, soaring gold and commodity prices, the very steep yield curve, and rising breakeven inflation rates on TIPS). It is an over-supply of money that debases a currency's value, leading to a general rise in the price level, just as an oversupply of houses relative to housing demand has led to a significant decline in housing values in recent years.

So while there is no obvious evidence that the Fed has committed a major inflationary faux pas, there is evidence to suggest that inflation is headed higher. And although banks have yet to utilize their huge stock of excess reserves to greatly expand the money supply, there is no reason to think that won't happen in the future, nor any compelling reason to think the Fed will be able to respond (by cancelling QE2 and/or withdrawing reserves) in time to prevent banks from doing so (e.g., how aggressive can the Fed get if the economy is still struggling to recover?). Conclusion: investors need to be prepared for higher inflation, but there is no reason yet to panic.The chart below shows a 16-year history of M2, in order to underscore the point that to date, there has been no unusual expansion in the amount of money sloshing around the economy. M2 has grown about 6% per year on average since 1995. Over that same period, the GDP deflator (the broadest measure of inflation) has risen about 2% on average, and real GDP has increased about 4.6% per year on average (all compounded, by the way). In other words, the amount of money in the economy actually has grown by a little less than the growth in the nominal size of the economy (i.e., 6% vs. 6.7% per year).

There are still some important questions to be answered, however. How can there not have been any new money printed, if the Fed has purchased almost $1.5 trillion of Treasuries and MBS since late 2008? What happened to the $1.5 trillion that the sellers of those securities received? Can the quantitative easing process continue indefinitely without inflationary consequences? What will happen if/when quantitative easing stops?

The short answer to the first question (why no new money?) is that at the end of the day, two things happened: 1) banks were willing to hold on to the new reserves, and not use them to increase their lending, and 2) the world in aggregate did not want to increase its dollar borrowings. Another way to put this is that the extra reserves satisfied the world's demand for additional safe and liquid assets. At the same time, the Fed effectively swapped reserves (a kind of T-bill equivalent) for T-Notes and MBS, thus shortening the maturity of federal debt and reducing the private sector's exposure to rising interest rates.

Can this continue indefinitely without inflationary consequences? I doubt it. But there is a certain vicious-cycle aspect to all this that is troubling. The more the government borrows (with the federal deficit on track to hit 10% of GDP, a very large number by any standard), the more the government spends; the more the government spends, the less efficient the economy becomes; the less efficient the economy, the slower it grows; the slower the economy, the fewer attractive investment opportunities there are, and thus the more attractive Treasury debt becomes, even if interest rates are very low relative to inflation. This same dynamic may help explain why Japan has had deficits of more than 10% of GDP for many years, yet the yields on government bonds remain extraordinarily low and economic growth has been disappointingly slow.

Is the end of quantitative easing going to be painful? Not necessarily. The end of QE2 means only that the Fed will stop swapping reserves for longer-maturity securities. There will still be a mountain of excess reserves in the system. Even if the Fed were to start "tightening" immediately after the end of QE2, that "tightening" would hardly be considered problematic, since it could take years to reverse all the injections of reserves. And in lieu of actually reverse its reserve injections, the Fed could simply decide to pay a higher rate of interest on existing reserves. This would have the effect of raising short-term interest rates without reducing the supply of reserves. The steepness of the yield curve is proof that the market is already braced for short-term interest rates to rise by hundreds of basis points. The issue is not whether the Fed will tightening or by how much they will tighten; the issue is when and how fast they will start raising rates.

It is entirely conceivable that a rise in interest rates that results from a Fed tightening will have the effect of increasing the world's demand for longer-maturity securities, thus obviating the need for the Fed to continue swapping reserves for longer-maturity securities.

I hope it's clear that I'm trying to take an objective and dispassionate view of things. There is reason to be concerned, but not yet any reason to panic.

UPDATE: I want to clarify my views on inflation, since on the one hand I argue that the Fed hasn't committed an obvious monetary policy error (because M2 growth is still normal), but on the other hand I note the symptoms of rising inflation (weak dollar, rising gold and commodity prices) and worry that it will continue to rise. Contrary to what some conclude, I am not saying we don't have an inflation problem. I think that 6% M2 growth, if it persists, will be a strong force limiting the rise in reported inflation to 10% at the most, but even 5-6% inflation is enough to qualify as a problem in my book. With 6% M2 growth, inflation could exceed 10% only if we see a meaningful decline in money demand (M2/GDP) and a pickup in M2 velocity (GDP/M2). That is not impossible at all, but it has yet to occur.

Housing update--waiting for the rebound

Housing starts have been bouncing along the bottom for over two years now, after a record-setting collapse from 2005 through 2008. The industry has been in a deep slump that has lasted over 5 years. Residential construction is now only a mere 2% of GDP. If it were going to contract even further, you would think it would have happened by now.

I see the very low and flat trend of starts over the past two years as a good indicator that the housing market has found a market-clearing price and a market-clearing level of activity. Major adjustments have been made, and enough time has passed for the healing process (reducing the level of unwanted housing inventory) to be well underway. For the past two years, housing starts have been far below the level needed to keep up with population growth; therefore, it is only a matter of time before we see signs of a housing shortage and a renewed uptrend in prices.

Monday, April 18, 2011

Keeping things in context

Markets get jittery at times, and when they do it's helpful to review the fundamentals. As the top chart shows, swap spreads haven't budged at all in recent weeks, and are only slightly higher today, despite the headline news to the effect that the official outlook for the U.S. economy has been downgraded by S&P, and Greece is on the cusp of a default (which I anticipated a few months ago, based on the behavior of swap spreads and sovereign debt spreads). Low and relatively stable swap spreads mean that systemic risk is also low. Whatever is going on does not pose a serious threat to the health of the economy, or to the financial markets. Europe is going to have to digest a Greek default, but it shouldn't prove to be the end of the world.

As the second chart shows, the Vix index has moved up of late, but it's a pretty minor case of the jitters when looked at in the context of the past few years.

As the third chart shows, equity prices have been recovering to their long-term trends (choose whichever trend growth line you want, the result is the same), but still have a ways to go before raising valuation questions. The equity market has not overshot, and is not overpriced, as I've been arguing for quite some time.

We're still climbing walls of worry, and today's worries should not be too difficult to overcome.

Why smart investors ignore the ratings agencies

Today we discover that the outlook for the U.S. economy has suddenly deteriorated, according to the analysts at Standard & Poor's:

Ratings agencies rarely are the first to uncover important changes to the fundamentals behind a security or a country. More often than not, they are the last ones to figure out what is going on. Smart investors need to understand and react to changing fundamentals long before they are revealed in a rating agency press release. Ratings agencies cannot pay enough to hire staff smart enough to routinely beat the market.

The irony of today's announcement is that we are not on the cusp of some new and serious deterioration in the fiscal fundamentals of the U.S. economy. On the contrary, we are now on the cusp of what could prove to be a new and very positive trend in the fiscal fundamentals. For the first time in many years, Congress seems finally aware that it must make some serious attempt to cut spending. If the analysts at S&P were on top of their game, they would have upgraded the outlook for the U.S. today.

"Because the U.S. has, relative to its 'AAA' peers, what we consider to be very large budget deficits and rising government indebtedness and the path to addressing these is not clear to us, we have revised our outlook on the long-term rating to negative from stable," the agency said in a statement.If large U.S. budget deficits and rising government indebtedness are news to you, then you shouldn't be making investment decisions. A smart investor doesn't need to wait for S&P to figure out that the U.S. government has a huge problem—that problem has been obvious for at least the past two years. What is amazing is that the market today had a negative reaction to the S&P announcement of the obvious. That sounds like a buying opportunity to me.

Ratings agencies rarely are the first to uncover important changes to the fundamentals behind a security or a country. More often than not, they are the last ones to figure out what is going on. Smart investors need to understand and react to changing fundamentals long before they are revealed in a rating agency press release. Ratings agencies cannot pay enough to hire staff smart enough to routinely beat the market.

The irony of today's announcement is that we are not on the cusp of some new and serious deterioration in the fiscal fundamentals of the U.S. economy. On the contrary, we are now on the cusp of what could prove to be a new and very positive trend in the fiscal fundamentals. For the first time in many years, Congress seems finally aware that it must make some serious attempt to cut spending. If the analysts at S&P were on top of their game, they would have upgraded the outlook for the U.S. today.

Friday, April 15, 2011

Consumer price inflation is heating up

Today's release of March consumer price statistics was unsurprising to the market, with headline inflation coming in as expected (0.5%), and core inflation coming in a bit below expectations (0.1% vs. 0.2%). On a year-over-year basis, headline inflation was 2.7%, while core inflation was a mere 1.2%. Both measures are below their long-term averages.

But looking under the surface, the news is not all that rosy. Over the past six months, the CPI has increased at a 4.7% annualized rate, well above its long-term average, and reminiscent of the heady inflation we experienced in the 2004-2007 period. Over the past three months, the CPI is up at a 6.1% annualized rate. It's thus quite likely that the year over year CPI figure will exceed its 30-yr average (3.1%) by a comfortable margin before this year is out.

Even the core CPI is showing some underlying acceleration, with prices up at a 2% annualized rate over the past three months, and a 1.4% annualized rate over the past six months. It is noteworthy that both the core and the headline rates of inflation are accelerating at the same time. If monetary policy were non-inflationary, then the strength in food and energy prices that are driving the headline inflation index higher would be offset by declines in non-food and energy prices. But that is not happening—all prices are accelerating. This confirms that monetary policy is in fact accommodative, and that is exactly what the Fed is trying to achieve. The Fed wants inflation to move higher, and they are getting their wish. There is every reason to believe that this will continue for at least the balance of this year, since monetary policy operates with a lag and the Fed has made no move yet to tilt policy in a restrictive direction.

Investors will be interested in the behavior of the non-seasonally-adjusted CPI, since the interest payment on TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) is based on changes in that measure of inflation, with a two-month lag. The chart above shows the 3-month annualized rate of change of the CPI (nsa). It also illustrates the seasonal tendencies in the CPI: inflation typically reaches a low point around the end of every year, then a high point around March-April of every year. As should be evident, the seasonal low last December was a good deal higher than it has been for most of the past decade, and the recent high is almost as strong as any we have seen in the past two decades. In the first quarter of this year, the raw CPI is up at a 8.1% annualized rate. This means that the inflation adjustment that TIPS receive will be unusually strong on an annualized basis over the next few months, and possibly for longer.

The ongoing rise in China's inflation rate is making headlines today, but U.S. inflation is not too far behind, as this chart shows. It's not surprising that inflation should be moving higher both in China and the U.S., since China has essentially outsourced its monetary policy to the U.S. Federal Reserve by pegging the yuan to the dollar. Chinese inflation is somewhat more volatile than ours, and that is also not surprising since its economy is smaller and less burdened by long-term supply and labor contracts. If China has an inflation problem, then so does the U.S. It will just take longer for the problem to become obvious in the U.S.

Industrial activity enjoys strong growth worldwide

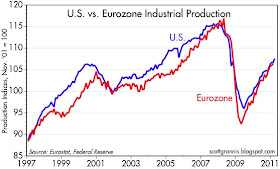

Since hitting bottom in June 2009, US manufacturing production has risen at a 7.4% annual rate, and has now recovered about half the ground that was lost to the 2008-2009 recession. That still leaves a lot of room for improvement, but there is as yet no sign that the pace of growth has diminished. At the current rate, manufacturing production will have made a full recovery within the next 18 months.

As this next chart shows, U.S. industrial production has been growing at about the same robust pace as Eurozone industrial production since the end of the recession, with both up at about a 5% annual pace in the past six months. The recovery is proceeding at a decent pace almost everywhere, and there is no reason at this point to doubt that this will continue. To be sure, the level of industrial and manufacturing activity remains depressed relative to previous highs, but it is the change on the margin (which is proceeding at an above-average rate) that is the important thing to focus on. Things are getting better at a decent clip, and will likely continue to do so. There are lots of good things to look forward to.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Swap spreads reflect low systemic risk

Swap spreads are excellent leading indicators of systemic risk, and thus very important things to track, which is why I continue to update this chart from time to time. As the chart suggests, conditions in the U.S. are just about optimal from a systemic risk standpoint: there is no shortage of money, default risk is low, and bank/counterparty risk is minimal. Conditions in Europe are still a bit unsettled, but they are slowly improving; the market continues to worry about sovereign debt default risk and its possible spillover effects, but swap spreads are saying that this risk is manageable and unlikely to prove seriously contagious.

Producer price inflation continues to accelerate

At the producer level, rising inflation is now unmistakable and indisputable. Even excluding food and energy, producer prices have been rising at a 2% annual rate since the beginning of last year, after rising by only 0.9% in 2009. Moreover, core producer prices rose at a 4.2% annualized pace in the first three months of this year.

This chart plots the producer price index on a semi-log scale, in order to highlight the different inflation regimes of the past several decades. Producer price inflation now appears to be accelerating beyond the 3.5% annual pace which prevailed from 2004 through last year, and far beyond the 1.7% annual pace which prevailed for the preceding 20 years. Over the past six months, the PPI is up at an annualized pace of almost 11%; over the past three months, prices have risen at an astounding 13% annualized pace.

These charts are an early-morning wakeup call that continues to be ignored by groggy Fed chairmen.

Weekly claims point to continued, but slow progress

First time claims for unemployment last week unexpectedly jumped, but this is entirely within the range of normal volatility for this statistic. On a four-week average basis, which is the preferred measure since it helps deal with the frequently-occuring problem of random blips, there is no sign of any meaningful change in what still appears to be a declining trend.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Higher interest rates will not be bad for stocks

Many observers and investors worry that stocks are going to be hit when the Fed starts to raise interest rates, especially if they move too soon to tighten. I've maintained for a long time, in contrast, that an early tightening of monetary policy would be good for stocks. This chart shows that investors' fears are not necessarily well-founded.

The ECB last week surprised the world by moving sooner than expected to lift its short-term interest rate target. I wrote last week that this was a good thing, and noted that pre-emptive monetary policy tightenings have been very good for the euro, the Aussie dollar, and the Canadian dollar.

The chart above extends that observation to the stock market. German 2-yr yields, which are the market's best guess for what the ECB's target rate will average over the next 2 years, have soared from a low of just under 50 bps in June, 2010, to now almost 190 bps. This move was driven by the ECB's sooner-than-expected tightening of monetary policy, and the rise in rates closely parallels the new-found strength of the European stock market.

This is not surprising, of course, since a central bank's moves are almost always a complicated dance between the market's perception of the economy's strength, and the central bank's perception of that same strength. Sometimes the market signals the central bank that a move is Ok, and sometimes the central bank guides the market. In recent months the European economy is looking better, the central bank is more concerned that inflation might be picking up, and the market is happy that the ECB is not going to slip behind the inflation curve without a fight.

I would anticipate, therefore, that an earlier-than-expected tightening move by the Fed would be greeted with similar enthusiasm. Tighter policy would acknowledge that the economy is in better shape, and at the same time reassure markets that the Fed is anxious to stay on top of things, rather than fall further behind the inflation curve. Confidence in the future, and confidence in one's currency, are very important sources of support for equity prices.

Federal spending again outpacing revenues

Here's my monthly update of the Federal government's finances. After some 18 months of improvement, during which time spending was restrained and revenues grew at a respectable rate—thanks to rising employment, strong productivity growth, strong corporate profits and a rising stock market—spending has once again perked up, sending the 12-month deficit to $1.4 trillion.

The recent budget agreement will do little to change the reality of a looming fiscal trainwreck. And even if the fiscal gap is eventually closed via higher taxes, the burden of government, as Milton Friedman taught us, is found in spending, not taxes or borrowing. If the government continues to spend 25% of GDP, the impact on the economy will not be mitigated by taxing more and borrowing less. Indeed, taxing more would probably be harmful to the economy in the long run, since it would immediately reduce the after-tax incentive to work and invest. Plus, as my mentor Art Laffer always used to say, if you had the choice of paying more taxes to the government or buying Treasury debt, wouldn't it be much better to lend the government the money? At least then you would have the hope of getting your money back, and with interest. In the end, whether the government borrows 10% of GDP or taxes an extra 10% of GDP, the federal government will end up spending the extra money in a way that will surely be less efficient and more wasteful than if the money had remained under the control of private interests. Friedman also reminded us that you never spend someone else's money as frugally and wisely as you spend your own.

The long-term outlook for the economy will only improve to the extent Congress is able to restrain the growth in spending. As I've pointed out before, simply freezing spending at current levels would balance the budget in about 5 years.

I think this can be done, and I think the recent budget agreement was the first step in the right direction. I note that the whole nature of the fiscal debate has changed 180º: the question now is how much and what to cut, not whether to cut spending. Consider Obama's amazing chutzpah when he praised the recent deficit reduction, just months after proposing the most outrageous deficit-ridden budget in recent memory.