Friday, May 28, 2010

Deflation and inflation are alive and well

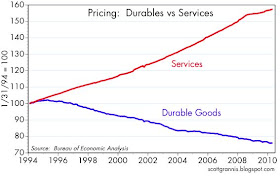

Over the past 16 years the U.S. has experienced a unique condition: the persistence of both inflation and deflation at the same time in two major sectors of the economy. This chart compares the behavior of two of three major subcomponents of the Personal Consumption Deflator: one covers the price of services, which in turn is largely driven by the inflation component of labor costs (and here I note that the PCE deflator rose 40% over the period covered by this chart), and the other covers the price of durable goods (e.g., cars, computers, appliances, TVs, equipment). (The third subcomponent is nondurable goods.) Never before, since the data were first collected in 1959, have these two price indices moved in opposite directions.

What this chart is saying is that consumers' purchasing power, when it comes to manufactured goods, has effectively increased by a lot, mainly because wages have been rising in both real and nominal terms, while the cost of durable goods has been falling. A simple example: for $1000 today you can buy a computer that can do things that not even a computer costing $1 million could do 16 years ago. The widening gap in this chart is a graphical representation of prosperity, where an hour's worth of labor buys more and more things. The difference between these two lines amounts to an increase in consumer purchasing power of a little over 100%, which in turn is solely due to a change in relative prices. The change in relative prices, in turn, is due primarily to the increased productivity of labor. The average worker today (and around the world) is able to produce far more than ever before with a given amount of work. In short, this chart is showing us just how much more valuable labor has become relative to things.

Chinese imports undoubtedly play a key role in this massive and unprecedented divergence of prices. Thanks to the hugely increased productivity of Chinese workers, U.S. consumers can now devote a greater and greater share of their income to things other than durable goods. (Unfortunately, healthcare and government would appear to be absorbing much of this increase.) Currency fluctuations have nothing to do with this, by the way: the dollar has fallen in real terms, relative to a trade-weighted basket of currencies, by about 5% over the period of this chart, so that would have the effect of increasing somewhat the price of imported goods.

The next time you find out that repairing your watch or your computer or your pocket digital camera costs almost as much as buying a new one, remember this chart.

Inflation remains tame, but the future remains uncertain

News from the inflation front continues to be quite benign, despite the numerous signs of rising inflation pressures that I have been citing since early last year. This chart shows the headline and core measure of the Personal Consumption Deflator, arguably the most comprehensive measure of inflation at the consumer level, and also the Fed's favored indicator of inflation. Some years ago the Fed established a range of 1-2% for this indicator, and by this measure inflation has been within its target range for the past 18 months. Prior to that, however, inflation was consistently above its target from 2004 through 2008. Over the past 5 years, the PCE deflator has risen at a 2.2 annualized rate, while the PCE core deflator is up at a 2.0% annualized rate; so when viewed from a long-term perspective, the Fed is finally on the verge of getting things right.

Ordinarily I would cheering this news. After all, from a supply-side perspective low and stable inflation is of paramount importance, since it provides a fertile field for confidence in the currency and for the investment that fuels growth and job creation. However I continue to be concerned about the potential for rising inflation, if for no other reason than the fact that monetary policy is in totally uncharted waters given the massive expansion of bank reserves in the past 20 months. Traditional indicators of monetary error such as gold (up 370% in the past 10 years and inches from a new all-time high), the value of the dollar (only 5% above its all-time low in inflation-adjusted terms relative to a large basket of currencies), real interest rates (the real Fed funds rate is negative), and the yield curve (still historically steep), suggest that at the very least the Fed is erring on the side of ease, and they have been very upfront in admitting this.

So while the official inflation numbers are almost as good as one could hope for, one's confidence in the future behavior of inflation cannot be very high. There is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the inflation picture, and that is not good. Thus, I consider monetary policy to be acting like a headwind to the economy, keeping growth from being as robust as it otherwise might be. Fiscal policy is another headwind, sapping the economy's strength by redistributing money from the most productive to the least productive.

Most of the supply-siders I know share these views. Interestingly, they run completely counter to the views expressed by many mainstream economists, who see fiscal and monetary policy as important sources of stimulus. So important, moreover, that they worry terribly that the economy is effectively on life-support and could not survive even the slightest reduction in monetary or fiscal stimulus. If nothing else, it's fascinating how reasonable people can take diametrically opposing views of the facts and come to similar conclusions: namely, that while the economy is recovering, we are unlikely to experience a robust recovery, and there are many reasons to worry. And that's why I think that we are still in a bull market, because true bull markets always have to climb one wall of worry after another. Optimism is in short supply.

Thursday, May 27, 2010

Corporate profits still look strong

Along with today's latest revision to Q1/10 GDP, we also received the initial estimate of corporate profits. In the year ending March '10, adjusted corporate profits after tax rose 24% from a year earlier. Compared to profits in 1998, when the S&P 500 was trading at approximately the same level as it is today, profits today are about twice as high. Looked at another way (second chart), profits as a % of GDP were about 6.5% of GDP in 1998, whereas today they are 7.7%, a level that rarely has been exceeded in the past 50+ years. Of course, many would argue that the market was entering bubble territory in 1998, but if even if that were indeed the case (though it was not obvious back then, as I recall), then surely equities are not overvalued today.

As the last chart shows, the recent strength in profits is by and large coming from nonfinancial domestic corporations, the meat-and-potatos sector of the economy, if you will.

I look at these facts and come away thinking that the corporate profits picture looks pretty darn impressive, especially considering how much the economy has been struggling in the past year or two. Equities are just not getting the respect that these numbers suggest they deserve. (Note that I am using the National Income and Products Accounts measure of profits, not the profits that are commonly used to calculate PE ratios. In my experience NIPA profits are much less volatile and more reliable, since they include all corporations and they are adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption allowances, so they are effectively equivalent to true economic profits. I owe a big HT to Art Laffer for this, since he has been following this series closely for as long as I can remember.)

The 10% GDP output gap

With today's release of the second estimate of GDP numbers for Q1/10—which resulted in a very minor downward revision of annualized real growth from 3.2% to 3.0%—I thought I would revisit this chart, which compares the path of real GDP to a 3.1% annual growth path. My choice of a 3.1% growth rate harkens back to Milton Friedman's Plucking Model of growth, which I discussed in a post almost one year ago. In essence, his theory is that the U.S. economy has a built-in ability and/or desire to grow by a certain amount every year, and when it fails to achieve that, because of a recession-provoking disturbance of some sort, then it has a strong tendency to snap back to that long-term trend line once the economy has adjusted to the disturbance. This behavior has been documented by the Atlanta Fed: the sharper the recession, the stronger the recovery.

If this theory holds true, then currently the economy is about 10% below where it really wants to be. This would ordinarily lead to an explosive recovery. I have been arguing for over a year now that we won't get the explosive recovery (in which the economy would grow by 6-8% for a few years), primarily because of the monumental amount of fiscal "stimulus" this time around that is holding back growth by making the economy less efficient. Instead, I've been looking for 3-4% growth, and that's what we've been seeing so far. I think a cessation of fiscal "stimulus" spending would give the economy a huge boost. Note that this goes directly counter to what conventional wisdom is saying; everywhere you look these days you see people worried that the fourth quarter of this year is going to be weak because stimulus spending is scheduled to drop.

The real problem with the "output gap" we have today is twofold: on the one hand it encourages the Fed to remain hyper-easy, out of fear that the gap exerts strong deflationary pressure on the economy; and on the other, it encourages Washington to "do something," like extend unemployment benefits (which only reduces the incentives of the unemployed to seek work) and otherwise spend money (which takes money from the private sector that could otherwise be put to better use). To the extent we can cut spending, I think the economy will be better off. And if the November elections are going to be as transformative as I think they will be, then the prospect of major cutbacks in the size and role of government in coming years should be a cause for celebration, because then the economy will have a much better chance of closing the output gap rapidly, instead of over the course of many years. And the sooner the economy starts perking up, the sooner the Fed is going to have to normalize (i.e., raise) interest rates. This won't be a problem either, because current interest rates reflect the market's pessimistic view of future growth. Stronger growth and higher rates should go hand in hand.

As fear subsides, prices should rise

The euro financial panic appears to be easing. Swap spreads are off their highs, and the implied volatility of equity options has dropped from a recent high of 48 to 30 today. This should allow substantial improvement in equity prices going forward. Europe hasn't solved its problem, but the market response to the problem has, in my view, been exaggerated. Our inefficient markets just don't have the liquidity and the transparency that's needed to keep volatility (and panics) at bay. The price of inefficiency is excessive volatility (and lots of sleepless nights). That's unfortunate, but the solution is not difficult: as the market better understands this weakness, natural market forces will be brought to bear on the problem. More and more investors will become willing to buy dips and sell rallies, and more and more will be willing to sell put and call options (both being equivalent strategies). Over time this will serve to dampen volatility, and it will help buy time until eurozone authorities figure out an intelligent response to the threat of banking system insolvency.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Shipping activity continues to be strong

I've showed these charts many times over the past year. Early in 2009 I thought the bounce in the Baltic Dry Index (a measure of shipping costs for bulk commodities in the Pacific region) was a good sign that the global economy was coming out of its 2008 slump. The Harpex Index (a measure of shipping costs for containers in the Atlantic) was a laggard, however, until just a few months ago, but it is now surging. With both indicators up significantly on the margin, it would appear that global economic activity is broadening and strengthening, and this provides a welcome counterpoint to the financial panic that is gripping Europe. Strong growth fundamentals provide an excellent source of fundamental support for European debt restructuring should it occur.

And while on the subject of European debt, here are some facts to help keep things in perspective. As my friend Mike Churchill notes, the combined GDPs of Greece, Ireland and Portugal total about 1% of global GDP, which is roughly $60 trillion. I note that Greece's sovereign debt of roughly $400 billion is about 1% of the global bond market, which is approaching $40 trillion. We're not talking about a lot of money here, even if Greek debt suffers a significant haircut in a restructuring. The main issue is whether debt-related losses are too much for the balance sheets of Europe's major banks to absorb. The rise in euro swap spreads that I highlighted yesterday confirms that this is the market's major source of concern; 2-year euro swap spreads closed at just under 80 bps today, and that is a sign of significant—but not yet fatal—concern over the counterparty risk inherent in the European banking system.

AAPL > MSFT

Today, Apple's market cap exceeded that of Microsoft for the first time ever ($222 billion vs. $219 billion). It's not the way I would have liked—Apple's stock has held up better than Microsoft's in the recent selloff—but it is nevertheless a milestone of sorts. Apple achieved this victory over its long-time competitor by relentlessly innovating for the past 10 years: OS X (plus 5 upgrades), iPods, MacBook laptops, iMacs, Mac mini, Apple TV, iWork, iPhones, and most recently the iPad. Microsoft, meanwhile, has managed to achieve little more than one major upgrade to its operating system (Windows 7) after one failed upgrade (Vista).

Like so many others, I anxiously await the next Apple innovation.

Capital spending is very strong

Business investment (new orders for capital goods) fell a bit in April from its March level, but thanks to upward revisions to previously released data, investment was actually up 4% versus the old level for March, and March numbers were revised up by 7%. Thus, as the charts show, capex has grown quite strongly over the past year; stronger in fact than at any time since the series began. I almost hate to say it, because I've said it so many times about different series, but this is clearly a V-shaped recovery, and it's very positive since business investment is what produces the growth and jobs of the future. It's also a good sign that businesses confidence is returning, and profits are being put to good use. There's still a mountain of corporate profits that have accumulated over the years but haven't been spent, so this story could have very long and strong legs; corporate profits after tax have doubled since 1998, but the level of capex spending has not increased at all on net.

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

More signs of housing market stability

According to the Case Shiller folks, housing prices in real terms in the top 20 U.S. markets have been roughly flat since the first quarter of last year. Real home prices have fallen 35% from their early-2006 peak, while over the same period 30-year fixed conforming mortgage rates have fallen by a full percentage point, reducing the cost of financing a home by 17%. Price adjustments of that magnitude are hugely significant in my book, and it would appear that they have been large enough to clear the market—large enough to deal with the oversupply of homes, and large enough to compensate for the effects of the recession on family finances. We are four years into this adjustment process, and that is a lot of water under the bridge. Unless there is another unforeseen shock to the system, it is very unlikely that prices will fall further. It's time to move on and stop worrying about the housing market.

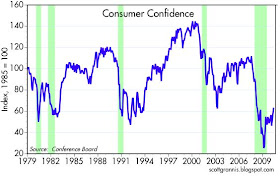

Consumer confidence is returning

It's reassuring to see consumer confidence on the rise, but it's ironic that this news coincides with the market's rather sudden loss of confidence (see my previous post). In any event, I doubt that Europe's brewing financial crisis is going to have a significant impact on the daily goings-on in the U.S. economy. The wheels of recovery are turning, and they are unlikely to be easily derailed.

Markets rush for the exits

Swap spreads are an excellent indicator of systemic risk. (See my basic swaps primer for more details.) Currently, swap spreads are saying that something is very wrong in Europe, and U.S. investors are getting very worried about a possible contagion. Sharply rising swap spreads reflect a primal fear among investors that counterparty risk is on the rise: it's as if everyone were rushing for the exit at the same time, attempting to reduce their exposure to the risk that sovereign defaults turn into major bank defaults. The market is suddenly very distrustful of nearly everyone's solvency.

The Vix Index is a good indicator of the market's level of fear and uncertainty. Fear and uncertainty started rising over concerns that a Greek default could trigger other defaults that could eventually throw a wrench into the Eurozone economy. Now those fears are being fanned by the merger of four failing Spanish banks, and rising tensions in the Korean peninsula that threaten to spill over into weakness in major Asian economies. So many problems that might have unpleasant consequences, what is an investor to do? Run for the exits.

The world's appetite for risk is suddenly less. Stocks are down, commodities are down, even gold is down from its recent high. Short-term Treasury bill yields both here and in Europe are extremely low as a result (0.15%).

I don't have any particular insight into how the world's problems can be resolved. What I do know is that the surge in swap and credit spreads, coupled with the surge in implied volatility, offer a powerful financial incentive to those brave souls willing to shoulder the risk that the world as we know it comes to an end. Disaster insurance is now expensive enough that many will decide to forego it, and many will decide to sell it. Swap spreads can't rise by much more or stay this high for much longer without there being some confirmation of the market's fears, in the form of massive bankruptcies and widespread economic destruction. Implied volatility could spike higher, as it did in late 2008, but already the potential return to selling options is becoming quite tempting.

Another thought: how can the market move so suddenly from being calm to being stormy? Greek credit default swaps were just over 100 bps about six months ago, and now they are 700, even in spite of the Eurozone's willingness to socialize the costs of Greece's debt burden with a $1 trillion bailout package. 2-yr euro swap spreads were 50 bps in early April, and today they spiked to 90 bps. Have the economic and financial fundamentals so suddenly deteriorated? Or is it that the market is just not liquid enough or deep enough or smart enough to handle just a tiny increment in perceived risk? After reading and absorbing the message of "Panic

Here's my take: Market inefficiency and misguided public policy, not a fundamental economic deterioration, are most likely the source of these wild price swings. The market is not well suited to dealing with the uncertainty that arises from sovereign blunders, so it offers outsized returns to those who are. I believe that sooner or later enough brave souls will be found to shoulder the risk; sooner or later politicians will stumble on the proper solutions—with the help of an outraged electorate; sooner or later the economic recoveries that are underway in all the nooks and crannies of the global economy will trump the pain of debt defaults. I don't see that the world is coming to an end, so I'm not going to rush for the exit.

Monday, May 24, 2010

Obama's ratings once again deteriorate, and that's good

A quick update on the Rasmussen polling results for Obama, which I've been tracking for over a year now. While Obama's overall approval rating a few months ago was a bit worse than it is today, I think the charts show that satisfaction with Obama has been on the decline since day one. Moreover, Rasmussen also finds that 63% of U.S. voters now favor the repeal of Obamacare, while only 32% oppose repeal. This is the highest level of opposition to date.

My guess is that cap and trade will not be successful. There are too many competing constituencies, and too much controversy surrounding the larger issue of global warming, for this to be successful. Plus, cap and trade essentially boils down to a big tax on carbon-based energy sources, and this is not exactly the sort of thing the economy needs right now. Add these considerations to the growing numbers of those who not only dislike but oppose Obama's initiatives, and you have a recipe for gridlock, even before the November elections.

With the exception of the $200 billion bill that Congress is trying to pass this week (which contains some tax hikes and extensions of popular tax breaks), we are unlikely to see more economy-damaging legislation this year, and that is good.

Another V-sign

It seems the world continues to fret that recoveries are fragile things, and that something like a Greek default could bring down the euro. While it's clear that the recoveries in Europe and in the U.S. are less vigorous than prior recoveries have been, there are still so many signs of a substantial recovery that I think it is very premature to worry about another relapse. This chart of the Chicago Fed's National Activity Index is just one more of the indicators that suggest this recovery is the real thing.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

The M2 myth: money is not in scarce supply

With the CPI having fallen a bit in April, and the equity market behaving as if a double-dip recession is in the cards, fingers are pointing to the very slow growth in M2 and warning of deflation and other dire consequences. Pundits can be mistaken, of course, so it's always best to do some homework. As of today's release, M2 growth, on an annualized basis, is 0.6% for the past 3 months, 0.5% for the past six months, 1.5% for the past year, and 5.1% for the past two years. The reason for the slow growth in the past year is that growth in the prior year was exceptionally fast, as should be clear from the first chart above.

For the past 15 years, M2 growth has averaged about 6% per year. Over the past two years it has only grown 5% on average, but it is still above what looks to be its long-term trend. For purposes of comparison, I note that since 1995 nominal GDP growth has averaged about 5% per year, and real GDP growth has been about 2.5% per year. Inflation has averaged about 2.5% as well, and has been relatively stable around that level. All of these are fairly unremarkable numbers, and about as stable, on average, as you could hope to see.

From these facts I conclude that there is no basis for the widespread concerns about the economy being starved for money, about deleveraging leading to a Japanese-style slump, or about deflation. As I've maintained all along, the strong growth in M2 in late 2008 was driven by a surge in money demand (and a big drop in money velocity), while the slow growth in the past year has been a sort of pay-back, with money demand declining and money velocity picking up.

On a final note, I see that the 3-month annualized growth rate of M2 has increased from a low of -1.4% four weeks ago, to 0.6% today. This, in the context of the level of M2 approaching its long-term trend, seems perfectly reasonable. The behavior of M2 going forward will tell the tale of whether we have too much money, or not enough. It will also be important to watch M2 velocity, since it has a long way to go to "pay back" its decline over the past year or so. If M2 velocity keeps rising and M2 growth also picks up, even modestly—which would not surprise me at all—we would have the essential ingredients for some monetary inflation.

Financial indicators still point to recovery

This chart has the best track record of signalling recessions of any that I'm aware of. The blue line is the real Fed funds rate, and the red line shows the slope of the Treasury yield curve from 1 year through 10 years. Every recession for the past 50 years has been preceded by a rise in the real Fed funds rate and an inverted (negatively sloped) yield curve. When real short rates are high and the yield curve is inverted, its because the Fed is aggressively tightening monetary policy, and this eventually strangles the economy.

Conditions today are the exact opposite, and point to continued recovery. The Fed is easy, real short rates are negative, and the yield curve is almost as steep as it's ever been (even though it has flattened somewhat today). It would be astonishing if a recession were to develop given how accommodative financial conditions are today. (And I note that conditions in Europe are quite similar to conditions here in the U.S.)

The Euro crisis reaches panic proportions

As panics go, the current one is a doozy, eclipsed in modern times only by the Lehman collapse and the Crash of '87. Is Europe teetering on the brink of collapse? I suppose anything can happen, but surely it can't be very likely.

I think the explanation for the current panic is that investors are simply very skittish and the market is not nearly as liquid as one would like to think. Hair-trigger stop losses can overwhelm the market when the going gets tough. The panic feeds on itself. Pundits predict another calamity in the making. European policymakers do stupid things like prohibiting naked short selling.

With panic selling of equities comes panic buying of Treasuries. German 2-yr Bund yields are down to less than 0.5% (US 2-yr yields are 0.7%). 10-yr Treasury yields are down 75 bps from their April highs. As this chart suggests (my interpretation), yields at this level only make sense if we are on the verge of another recession. Yet there are simply no signs of a recession that I can find. Central banks are still very easy, yield curves are still quite steep, corporate profits are strong, commodity prices are still quite high, swap spreads haven't widened significantly, and many areas of the global economy are experiencing V-shaped recoveries.

Sovereign yields are very low, implied volatility is very high, gold is very strong and the dollar is up sharply against other major currencies, but the classic precursors of a recession are nowhere to be found—all this makes sense only in the context of a panic. When the panic subsides, prices are very likely to rise again, as this last chart suggests:

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

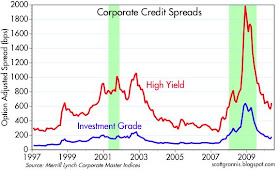

Spread update: not much to worry about

Expanding on the theme of my prior post, here is a quick look at the current state of swap and credit spreads. As is the case with most "risk assets," we see a modest correction in credit markets. US swap spreads have moved up, but from very low levels to levels that are easily within the range of "normal." As the second chart shows, the rise in US swap spreads has pretty much followed the rise in euro swap spreads, suggesting some degree of contagion from Eurozone credit concerns; after all, if a large European bank should go belly up, it would surely be of concern to its US counterparties. But as my friend Mike Churchill reminds me, euro swap yields (as shown in the third chart), have been falling consistently throughout the developing Greek crisis. In other words, the rise in euro swap spreads has been driven mainly by a collapse in government yields, which is more a sign of investors seeking safety than it is of investors fleeing the market in general. Funding costs for most qualified borrowers have been declining all year, so the rise in swap spreads does not pose any threat to economic activity.

Meanwhile, 10-yr US swap spreads are trading at a mere 6 bps (vs. 28 bps in Europe), which is still quite low from an historical perspective. Consequently it would appear that the market is thinking that this is a near-term problem, not an enduring or structural problem.

Corporate credit spreads have also moved up, as shown in the fourth and fifth charts, but so far the correction doesn't appear to be significant or particularly disturbing. If we assume that swap spreads continue to be leading indicators for spreads in general (as I have been arguing since October '08), and given that swap yields are still declining, then there is little reason for alarm. The market is certainly uneasy, but that seems more likely due to a case of nerves rather than to anything concrete.

Is the commodity selloff significant?

A friend asked me yesterday if I saw any signs of concern in the commodity markets. Could the broad-based decline in commodity prices in the past month be signaling an economic slump? Could the worries over Greek debt and the future of the euro be spilling over into another round of consumer and corporate retrenchment around the world?

So I pulled together these charts of various commodity prices and indices and updated them with the latest figures. I think the message of every one is basically the same: yes, there's been a bit of a selloff, but it doesn't look particularly large from an historical perspective, and prices remain relatively elevated. In the case of gold (last chart), the recent decline is almost undetectable, and gold is the commodity most likely to be driven by speculative (and forward-looking) activity. The CRB spot commodity index is probably the one least influenced by speculative activity (since only a few of its components have futures markets attached to them), but it too has suffered only a minor correction of late.

Meanwhile, the dollar has experienced a pretty significant rally in the past month, coincident with the modest selloff in commodities. This is not unusual at all, since the value of the dollar and commodity prices have been inversely correlated for a long time.

Faced with the uncertainty of Greece and the euro, investors have retreated to the safety of the dollar and gold. Commodities have experienced a modest correction as the dollar has climbed, because commodity prices almost always respond that way to changes in the value of the dollar. If there's anything that stands out here, it is that the correction in commodity prices looks quite tame relative to the change in the dollar. And that, when combined with the very strong performance of gold, suggests that global liquidity is still in abundant supply.

Equity investors have been spooked as well. But note the big jump in the Vix Index, actually the biggest since those awful days of late 2008 when it seemed that the whole international banking system was on the verge of collapse. The biggest thing impacting the markets right now is that old familiar nemesis: fear, uncertainty and doubt. The rise in FUD is much bigger than any physical or financial sign of economic deterioration.

Bottom line: the most likely explanation for what is going on is this: the market is climbing one more in a series of "walls of worry." Today's concerns will eventually pass, to be replaced by a renewed focus on the many signs of renewed global growth.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

The political tsunami is underway

Message to big-spending incumbents:

Rep. Joe Sestak defeated five-term incumbent Sen. Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania’s Democratic primary election. Mr. Specter is the third incumbent in as many weeks to lose his re-election bid in an intra-party contest.

With 65% of precincts reporting, the Associated Press called the race for the two-term Mr. Sestak, 53% - 47%.

Mr. Sestak defied the party establishment, including President Obama, in mounting a primary challenge to Mr. Specter, who switched parties last year in part to improve his re-election prospects.

Rep. Sestak faces Republican Pat Toomey in the fall election.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703957904575252061587373610.html?mod=djemalertNEWS

This is huge. The people are very upset, and they are taking their revenge. At this point it seems difficult to underestimate the positive changes, from the perspective of a supply-sider or non-Keynesian, that will occur with the November elections. Very bullish.

Rep. Joe Sestak defeated five-term incumbent Sen. Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania’s Democratic primary election. Mr. Specter is the third incumbent in as many weeks to lose his re-election bid in an intra-party contest.

With 65% of precincts reporting, the Associated Press called the race for the two-term Mr. Sestak, 53% - 47%.

Mr. Sestak defied the party establishment, including President Obama, in mounting a primary challenge to Mr. Specter, who switched parties last year in part to improve his re-election prospects.

Rep. Sestak faces Republican Pat Toomey in the fall election.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703957904575252061587373610.html?mod=djemalertNEWS

This is huge. The people are very upset, and they are taking their revenge. At this point it seems difficult to underestimate the positive changes, from the perspective of a supply-sider or non-Keynesian, that will occur with the November elections. Very bullish.

One more attempt to repeal the law of gravity

In a few hours, Germany will introduce a "temporary ban on naked short-selling and naked credit-default swaps of euro-area government bonds." Presumably, this move is meant to calm markets by protecting them from the predations of greedy speculators. Predictably, however, it only makes matters worse. In the wake of the news announcement, the euro dropped, gold rose, government bond yields fell, implied volatility of equity options rose, and equities fell—all classic signs of a market suddenly more concerned about downside risks to the economy and financial markets. And it stands to reason, because announcing you're going to limit the market's ability to express downside risks tomorrow, only increases the market's desire to protect against downside risks today.

The only good news is that Germany's attempt to repeal the law of gravity (by supposedly limiting negative speculation), can be easily reversed. That's likely not the case with Venezuela's decision today to attempt to put a band around its sinking currency. Venezuela has already made two fatal mistakes, first by printing money (and thus fundamentally debasing its currency), and second by devaluing the currency but establishing a dual exchange rate for imports and exports (thus encouraging all sorts of shenanigans, like the over-invoicing of imports, that effectively funnel capital out of the country). You either respect your currency or you don't; the more you try to prevent it from falling by diktat or by exchange controls, the more you undermine confidence in the currency.

Banning naked short selling may make it harder for speculators to speculate on a Greek default, but it does nothing to change the fundamentals behind Greek debt. It does, however, interfere with markets by making them less efficient, and it heightens investors' concerns: do the regulators know something we don't? Thus Germany is taking steps that could needlessly prolong the crisis. That's unfortunate, but it's not the end of the world. The fundamentals of global growth are firmly in place and likely to carry the day once the dust settles.

The only good news is that Germany's attempt to repeal the law of gravity (by supposedly limiting negative speculation), can be easily reversed. That's likely not the case with Venezuela's decision today to attempt to put a band around its sinking currency. Venezuela has already made two fatal mistakes, first by printing money (and thus fundamentally debasing its currency), and second by devaluing the currency but establishing a dual exchange rate for imports and exports (thus encouraging all sorts of shenanigans, like the over-invoicing of imports, that effectively funnel capital out of the country). You either respect your currency or you don't; the more you try to prevent it from falling by diktat or by exchange controls, the more you undermine confidence in the currency.

Banning naked short selling may make it harder for speculators to speculate on a Greek default, but it does nothing to change the fundamentals behind Greek debt. It does, however, interfere with markets by making them less efficient, and it heightens investors' concerns: do the regulators know something we don't? Thus Germany is taking steps that could needlessly prolong the crisis. That's unfortunate, but it's not the end of the world. The fundamentals of global growth are firmly in place and likely to carry the day once the dust settles.

Greek Myths

John Cochrane has a superb op-ed in today's WSJ: "Greek Myths and the Euro Tragedy." Superb because he argues clearly and concisely that conventional wisdom on the subject of a possible Greek default, and how that might be really bad for the euro, is completely wrong.

"We're told a Greek default would imperil the euro. The opposite is true." A Greek default would only harm the euro if the ECB failed to act responsibly.

"A currency union is strongest without fiscal union." Giving investors the impression that other countries and the ECB itself stand ready to bail out profligate governments only creates moral hazard. Allowing Greece to default or restructure its debt would show the world that the ECB means business.

"... the euro's founders ... set debt and deficit limits. The problem is not that these limits were too loose. The problem is having them at all." The market is the best enforcer of limits on debt, not politicians. Those who borrow too much soon find that the cost of borrowing becomes prohibitive, and they then have no choice but to either reduce their spending or restructure their debt.

"We're told that a Greek default will threaten the financial system. But how? Greece has no millions of complex swap contracts, no obscure derivatives, no inter-twined counterparties. This isn't new finance, it's plain-vanilla sovereign debt." Those who read "Panic," the book I reviewed last week, will understand that this is a crucial point. The financial panic of '08 and early '09 was in large part driven by the market's lack of understanding of the risks inherent in complex derivative securities. In the case of Greek bonds, the risks are simple and straightforward.

"Letting someone lose money on sovereign debt is the acid test for the euro. If not now, when? It won't happen in good times, nor to a smaller country."

"The only way to solve the underlying euro-zone fiscal mess (and our own) is to slash government spending and to focus on growth. ... growth does not come from spending. Greece's spending over 50% of GDP did not result in robust growth and full coffers. At least the looming worldwide sovereign debt crisis is heaving 'fiscal stimulus' on the ash heap of bad ideas." This point is also crucial, as I have tried to point out before. Deficit-financed spending can never stimulate an economy, so slashing spending in order to reduce financing needs is not likely to kill an economy. It is likely, however, to improve investor confidence and economic efficiency, and those in turn become key ingredients for badly-needed future growth.

What this all means is that the market is likely overestimating the risks to Europe and the euro. The problem is not nearly as bad or intractable as the market seems to think.

"We're told a Greek default would imperil the euro. The opposite is true." A Greek default would only harm the euro if the ECB failed to act responsibly.

"A currency union is strongest without fiscal union." Giving investors the impression that other countries and the ECB itself stand ready to bail out profligate governments only creates moral hazard. Allowing Greece to default or restructure its debt would show the world that the ECB means business.

"... the euro's founders ... set debt and deficit limits. The problem is not that these limits were too loose. The problem is having them at all." The market is the best enforcer of limits on debt, not politicians. Those who borrow too much soon find that the cost of borrowing becomes prohibitive, and they then have no choice but to either reduce their spending or restructure their debt.

"We're told that a Greek default will threaten the financial system. But how? Greece has no millions of complex swap contracts, no obscure derivatives, no inter-twined counterparties. This isn't new finance, it's plain-vanilla sovereign debt." Those who read "Panic," the book I reviewed last week, will understand that this is a crucial point. The financial panic of '08 and early '09 was in large part driven by the market's lack of understanding of the risks inherent in complex derivative securities. In the case of Greek bonds, the risks are simple and straightforward.

"Letting someone lose money on sovereign debt is the acid test for the euro. If not now, when? It won't happen in good times, nor to a smaller country."

"The only way to solve the underlying euro-zone fiscal mess (and our own) is to slash government spending and to focus on growth. ... growth does not come from spending. Greece's spending over 50% of GDP did not result in robust growth and full coffers. At least the looming worldwide sovereign debt crisis is heaving 'fiscal stimulus' on the ash heap of bad ideas." This point is also crucial, as I have tried to point out before. Deficit-financed spending can never stimulate an economy, so slashing spending in order to reduce financing needs is not likely to kill an economy. It is likely, however, to improve investor confidence and economic efficiency, and those in turn become key ingredients for badly-needed future growth.

What this all means is that the market is likely overestimating the risks to Europe and the euro. The problem is not nearly as bad or intractable as the market seems to think.

Inflation is still alive and well

The Producer Price Index of finished goods in April fell 0.1%, but only after rising at a 7.3% annualized rate in the past six months, and 5.4% in the past year. Excluding food and energy prices, the core PPI has been rising at a fairly steady 1% annual pace since early last year. So food and energy prices have been the major sources of inflation for the past year, but that doesn't mean inflation is dead.

If monetary policy were being run with the objective of keeping overall prices steady, then a significant rise in the price of one good or service would necessarily result in a significant decline in the prices of some other goods or services. With the above chart we see instead that big increases in food and energy prices did not prevent all other prices from rising. To the contrary: I note that prices of intermediate goods ex-food and energy have risen at an 8% annualized pace over the past six months, and 5.6% over the past year, while crude goods prices ex-food and energy are up at a whopping 48% annualized pace in the past six months, and 50% in the past year. Consequently we can conclude that the Fed is not pursuing a policy designed to deliver price stability.

The fact that inflation is still alive and well despite the huge amount of economic slack that has prevailed for the past 18 months also casts even more doubt than already existed on the still-popular Phillips Curve theory of inflation. Surely, if inflation had anything to do with the unemployment rate (the Phillips Curve posits an inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and the rate of inflation), then we should have seen plenty of evidence of deflation by now. To be sure, there are sectors of the economy that are experiencing price declines, but as the PPI numbers show, the overwhelming majority of prices are rising.

I've been arguing for quite some time that inflation is alive and well, and I think this is a significant issue. That's because the market continues to be very concerned about the risk of deflation; I see this in the relatively low 1.25% breakeven spreads on 2-year TIPS; I see it in the relatively low level of Treasury yields in general (2-yr Treasuries at 0.8%, 5-yr at 2.2%, 10-yr at 3.4%); and in the Fed's continued concern over deflation risk (why else would they insist on keeping short-term rates at close to zero?). If the market and the Fed were to lose their preoccupation with deflation risk, then the outlook for the economy and for corporate profits would brighten considerably, and default risk would decline. This would be undeniably good news for stocks and corporate bonds, and very bad news, of course, for Treasury notes and bonds, and for mortgage-backed securities. Furthermore, I suspect that if the Fed acknowledged that deflation risk were dead, the gold market would get a big case of the willies, because that would mean that super-accommodative monetary policy—the lifeblood of quadruple-digit gold prices—was on its way out. By the same logic, this would be a boon for the dollar, which remains historically weak.

Housing market recovery underway

It is now abundantly clear that the U.S. housing market is recovering. From the all-time lows registered in April of last year, starts have now risen 40%. To be sure, the level of activity is still dismally low, but that a recovery is underway is virtually certain. The Bloomberg index of home builders' stocks has been saying the same thing for some time now, with the average stock up 125% from last year's low. Recovery skeptics have been telling me for many months that a true recovery can't happen without a recovery in housing; if they are right, then this is pretty good news indeed. Regardless, I view this as just one more of many signs that the economy is in recovery mode. The only item of debate at this point is how fast the economy will recovery, not if. I see no reason to change my long-held expectation of 3-4% growth, which amounts to a moderate recovery, albeit one in which a lot of V-shaped sector recoveries, like this, can be found.

Monday, May 17, 2010

The essence of the Tea Party: leave us alone

Ed Crane, president of the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote a nice editorial in last Friday's Investor's Business Daily about the failure of our elected officials to understand what the people really want. As he puts it, we have a failure to communicate:

The communication problem involves the accelerating realization on the part of many Americans that the essence of America, namely, a respect for the dignity of the individual, ... involves the government leaving the individual alone.

One of the classic examples of the failure of politicians to communicate with the citizenry is found in a video of Romanian tyrant Nicolae Ceausescu, giving what turned out to be his last speech to the teeming masses gathered in a square in Bucharest.

Oblivious to the mood of the people, Ceausescu is at his bombastic, self-important best until he realizes that the chants from the crowd below are not praise, but something rather to the contrary.

The Declaration of Independence says governments are created to secure our rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. In other words, to leave us the hell alone.

... this is the encouraging thing about the Tea Party movement. It is made up of average Americans who are sick to death of politicians regulating, taxing, controlling and limiting individual choice.

[Congressmen] think we sent them to Congress to solve our problems when we sent them there to see to it that we are left alone to solve our own problems. Add to that the fact that many of our problems have been created by Congress, and we have the basis for a healthy, peaceful revolution.

Where's the angst?

Given the plunge in the euro and the rampant speculation that the euro is history and its coming dissolution will prove very painful for the Eurozone economy, you would think that German equities, measured in dollars, would be in free-fall. But you would be wrong, as this chart shows.

Note that the two y-axes on the chart are scaled to be identical—the high point on each axis is 5 times the low point. One thing this reminds us of is that equities have rallied by a factor of almost 3 in the past 15 years. Not too shabby: the S&P 500 index has risen a little over 6% per year, compounded, since the end of 1994. Measured in dollars, Germany's DAX index has risen about 7% per year. So much for the collapse of Europe and the demise of equities.

The chart also illustrates how closely the equity markets of the U.S. and Europe have tracked each other over the years. Most of the variations shown in the chart are due to currency fluctuations, but these tend to wash out over time. In fact, the DM today is about 5% stronger than it was at the end of 1994. So the almost 20% decline in the euro since its Nov. '09 high against the dollar was not so much a collapse as it was a reversion to mean. Just keeping things in perspective.

UK industrial production turns up

The U.K. economy has been especially hard hit by the recession, but even there we can find some green shoots. Industrial production finally appears to be picking up, after being flat for over a year, a good indication that the economy is once again growing.

Friday, May 14, 2010

Currency update

The dollar has been in the limelight of late, benefiting from the euro's Greek travails, but as the last chart shows, the dollar in general is still pretty weak compared to where it's been in the past. And since gold is rising against all currencies, it makes more sense to say that the euro is weaker on the margin than the dollar, than to say the dollar is strong. The dollar is rising on the margin relative to a lot of currencies because the news here is somewhat better than the market had feared (i.e., less bad than expected), while the news overseas is either not continuing to improve or is underperforming optimistic expectations, particularly in Europe with the looming restructuring of Greek debt and the ECB apparently willing to monetize some debt to provide relief to struggling debtors.

The euro is still somewhat strong relative to its purchasing power parity vis a vis the dollar, but clearly weakening. The market is pricing in the increased likelihood that the political pressures for a Greek bailout will compromise the ECB's ability to run a tight monetary policy. The bearish euro trade likely has some room to room, because it would have to fall a lot more before it became cheap.

The currencies that are fundamentally strong these days, on a purchasing power basis (according to my calculations of PPP as shown on the charts), are the emerging market and commodity currencies. The Australian and Canadian dollars are about as strong relative to the dollar (on a purchasing power basis) as they've ever been, and ditto for the Brazilian real. But they do seem to be pushing their limits. When a currency is stretched relative to its PPP, the news has to continue to be awfully good (or awfully bad, as the case may be), in order to sustain those valuation extremes. So that means AUD and CAD are very vulnerable to any signs of a) weaker growth, b) tighter monetary policy in the developed world, or c) weaker commodity prices. Being long these currencies at these levels requires courageous conviction.

The yen is also fundamentally strong, but primarily because the Bank of Japan continues to pursue a very tight monetary policy—note that the steep upward slope of the PPP line reflects over three decades during which inflation in Japan has been significantly lower than in the U.S. The yen has a lot of tight money momentum going for it, but most of that is being counteracted by a persistently weak economy. Plus, at these levels it is clearly overvalued relative to its PPP and thus vulnerable to any bad news or just news that isn't completely supportive.

I've been moderately bullish on the dollar since last December (check my forecasts near year-end), but I am losing my enthusiasm as the dollar climbs. The Fed continues to insist it will remain super-easy for the foreseeable future, and that is a clear negative. At the same time I think the world is overdoing its concerns about the demise of the euro. The euro currency area is a bit larger than the U.S. economy; you don't just walk away from the euro because one relatively small country is having problems. Imagine telling the 300 million people in the U.S. that you're going to change from the dollar to the Can-dol-peso; the logistics alone, not to mention the political fury that would be unleashed, are mind-boggling. Europe has made its currency bed and it is going to have to sleep in it. At some point the majority of Europe is just going to have to ignore the Greek protests. And the Greeks are just going to have to trim their bloated government, and that won't be an unbearable task. For heaven's sake, all this government spending is a huge problem, so getting rid of it should be a huge relief.